A new law has been in force in Tajikistan since June 2024, which stipulates that it is strictly forbidden to wear clothes ‘alien to Tajik culture’. It is part of a series of restrictive laws that have been President Emomali Rahmon’s policy for more than two decades, aimed at preventing the strengthening of Islam in Tajikistan. This ex-Soviet country borders Afghanistan to the south and is situated in the region of Central Asia amongst Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. Even after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Tajikistan maintained close ties with Russia, which it now fears will be strained following the terrorist attacks on Moscow’s Crocus City Hall by Tajik nationals in March 2024. Over 90 percent of Tajikistan’s population identifies as Muslim, and while men are also called upon wearing nationalist clothing, it is women who are particularly discriminated by the new law. The ban on the hijab in Tajikistan once again highlights the special role of women in Central Asia as representatives of cultural identity, while equally evoking memories of a cruel chapter in the region’s history from around a hundred years ago.[1]

We are talking about a time when Tajikistan did not exist as a country as such; instead, the territory between the Caspian Sea and the Gobi Desert was known under the name of ‘Turkestan’—an allusive term for the homeland of Turkic peoples, influenced by both Islam and nomadism. The Russian Empire began colonizing Turkestan in the second half of the nineteenth century, but it was with the Bolshevik seizure of power after the October Revolution in 1917, that the establishment of the Soviet Central Asian republics began: A process of border demarcation within the region was ignited by Russians, which was to last from the mid-1920s until the end of the 1930s.[2] The fluid movement or consolidation of ethnic groups within the region was not considered sufficiently, and to this day, territorial conflicts between peoples in certain zones continue to flare up. In these turbulent times of power transition in Central Asia, women in the region found themselves inadvertently at the centre of ideological change. The extent to which women’s bodies became a projection screen between the modernity proclaimed by the Bolsheviks and the, for the most part, Islamic religious way of life that had existed in Central Asia until then can be understood by looking at the Hujum campaign initiated by Moscow on 8 March 1927, International Women’s Day.

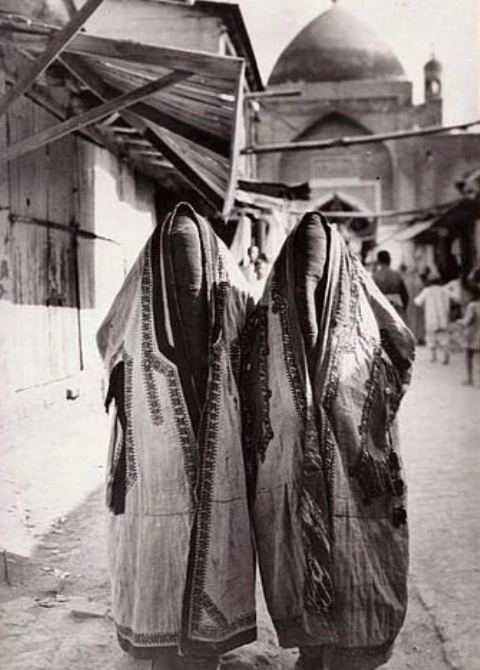

The Hujum campaign had the goal of ‘liberating’ and ‘emancipating’ Central Asian women by convincing them to voluntarily abandon the paranja, a traditional garment, predominantly worn by women in sedentary religious communities in Central Asia (mostly in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan). The ornamented robe covered the whole body and was usually worn in combination with a chachvon, a tightly woven net of horsehair hiding the face. The campaign as well as the polarization of a society around the object of the female veil, is also the main theme of Uzbek director Ali Khamraev’s 1971 film Without Fear (Без страха, Bes strakha), in which a Soviet Uzbek army officer is found wounded by a young local woman in rural Uzbekistan. They are then married, and the young man becomes the village governor. His colleagues in the Soviet city administration in Tashkent urge him to promote the unveiling of women in his village. But his wife, who is supposed to set a good example, refuses to take off her veil—she is too afraid of her father’s fury. Instead, another young girl steps forward and removes her veil in public; she is then killed by her enraged relatives. The tragic events depicted in the film are drawn from reality: scholar Marianne Kamp states that between 1927 and 1929, more than 2,000 women were killed by male relatives directly or indirectly linked to the unveiling campaign.[3] Although Khamraev commemorates the lives lost and the particularly vulnerable role of women during this period, the tone is not explicitly critical towards the Soviet-led reforms leading to the mass killings. Even more, it creates the impression that women’s rights in Central Asia were solely a Soviet concern, which was not the case.

Women wearing paranja and chachvon in the streets of Tashkent, Uzbekistan before the Soviet era. Source: reddit.com/r/muslimculture/comments/msvu7b/women_wearing_paranja_in_tashkent_uzbekistan/)

Film still, Without Fear (1971) by Ali Khamraev (original title: Без страха, Bes strakha). Source: www.youtube.com/watch?v=2q0mkV42iJ0

In the early twentieth century in Central Asia, there were indeed initiatives for more inclusive treatment of women. A prominent example, though little known outside of the region, are the Jadid reformers. The group sought to establish a modern Islam in Central Asia similar to that which was beginning to take shape in neighbouring Muslim-oriented countries such as Iran and Turkey. Historian Adrienne Edgar points out that the governments of these countries were able to rhetorically link the emancipation of women to the rise of a young and modern nation. Their integration into the labour market was seen as essential to nation-building, and their detachment from the domestic sphere as inevitable. It is also known that the Jadids initially joined the Communists voluntarily because they recognized similar goals in the Bolsheviks’ plans for the role of women in society and hoped for support in implementing their goals. However, as the Jadids were essentially nationalists—they envisioned the creation of a modern state in Turkestan, quite contrary to the interests of the newly established Soviet power.[4]

If we look at the rest of the Muslim world in the same period, in the French-ruled colonies of Morocco and Tunisia, and in British-occupied Egypt and Palestine, the situation was quite different: the colonial rulers had little interest in emancipating local women, fearing mass mobilization. In addition, there was another reason why they did not interfere much with traditional structures: the differences between European and so-called ‘Oriental’ peoples were seen as simply too large for western ways of life to be adopted. The emancipation of women remained mere rhetoric, used to legitimize colonial rule. With regard to the Hujum campaign, Edgar further notes that Bolshevik reforms in Central Asia in the early twentieth century were in many ways similar to those of young Muslim-oriented nations, as the integration of women into the labour market across the USSR was also one of their primary goals. In this context, Soviet ideology promoted women’s identification with the political values of socialism over those of their family background. The Bolsheviks hoped to mobilize Central Asian women by reinforcing negative sentiments towards religious laws and traditional patriarchal structures. Imposing such reforms from afar emphasized the already established hierarchy between Moscow and the regions it patronizingly referred to as the ‘East’; these reforms took on an imperial character and were, therefore, met with such fierce local (male) resistance.[5]

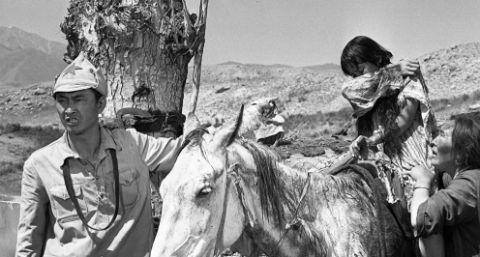

In Andrei Konchalovsky’s film The First Teacher (Первый учитель, Pervyy uchitel), Soviet Orientalism and its pejorative view of the Central Asian subject as uneducated and primitive is particularly evident. The drama released in 1965, is set in a Kyrgyz village at the end of the 1920s and Soviet re-education measures aimed at Central Asian peoples are negotiated and fought once more over the life and body of a local woman. The film stars fourteen-year-old Altynai as one of the first children and only girl to attend ‘Dyushen’s school’, which the children affectionately named after its founder. A young socialist and former Soviet railway worker, Dyushen can barely read or write himself but is convinced that children need to be educated and sets up a school in an old barn. However, his initiative is met with widespread incomprehension by the villagers, especially the relatives of Altynai. She is instead sold to a much older man to become his second wife. Thereupon, Dyushen kidnaps Altynai from her captivity and takes her to the local railway station. He tells her not to return and instead to live a modern life in the city, making her promise to study and go to university later. During their emotional farewell, he proclaims her ‘the first liberated woman of Central Asia!’

Film still, The First Teacher (1965) by Andrei Konchalovsky (original title: Первый учитель, Pervyy uchitel). Source: www.imdb.com/title/tt0059585/

From today’s perspective, one might think that the reception of Soviet films depicting Central Asian peoples as ‘primitive’ would have been differentiated at the time—celebrated in Russia and angrily rejected by those represented. But this is unlikely. Films like Andrei Konchalovsky’s The First Teacher, based on a novel by Kyrgyzstan’s most famous writer Chingiz Aitmatov, were popular USSR-wide. By comparison, Aitmatov’s story of the same name is primarily about the unfulfilled love between Altynai and her teacher, while the film adaptation focuses on the liberation of an indigenous, oppressed girl by a passionate follower of Lenin. Nevertheless, the power of representation is particularly evident in this film—it taught those depicted how to perceive themselves, and this was not very difficult as the evidence ‘spoke’ for itself: already in 1922, at the time of foundation of the USSR, gender equality was enshrined in the Soviet constitution and abortion legalised in its early days. Although the Central Asian states did not experience an economic boom until after the Second World War, prosperity eventually increased there too, thanks to the establishment of a system dependent on Russia as an importer of their raw materials and food supplies. The 1960s and 1970s saw a sharp rise in the number of women attending universities in Central Asia, and an ever-growing percentage of women pursuing careers alongside their domestic responsibilities. Shortly before the collapse of the Soviet Union, the female employment rate was at almost 100 percent.[6]

Finally, another layer of analysis to the representation of Central Asian women in Soviet films can be added: the two films mentioned were produced during the Cold War; therefore, the messages they carried were aimed not only at a Soviet audience, but also at an international one. Soviet films were not widely distributed outside the USSR during this period, but instead Moscow and Tashkent played host to the international film scene through the establishment of annual film festivals in their respective cities. Between 1968 and 1988, the Tashkent Festival of Asian, African and Latin American Cinema invited filmmakers and actors from the so-called ‘Third World’ or non-aligned states, to visit Uzbekistan and to forge new alliances with the Soviet Union. The films screened in Tashkent were wide-ranging, but through Masha Salazkina’s research we know that narratives of women’s ‘emancipation’ during the Soviet Union, especially those hailing from Central Asia, were prominent. As she states: “(…) women’s experiences were central to a large number of films screened at the festival and were repeatedly foregrounded in the festival reviews. In the context of Asian and African cinema in particular, the degree of women’s emancipation from the traditional patriarchal order became a litmus test of progress and a pivot point for envisioning the alliance of ‘progressive’ Islam and socialism. Central Asian cinema in this context occupied a position as an intermediary between Soviet and postcolonial models of the treatment of gender and sexuality (...).”[7]

However, Salazkina also stresses that the historical struggle of women during the Hujum period, its representation on screen, and the actual presence of women at the Tashkent Film Festival do not sit neatly together. Overall, there were only few women who were invited to present their films in Tashkent. The same applies to the presence of female film critics at the festival—not a single one of them took part in public lectures, debates, or round tables as the stage was left to the men. On the other hand, women were disproportionately represented among the live translators of the films, a particularly demanding task at the festival, though one that kept them out of the public eye and hidden behind translation booths. The women who were most visible within the festival were actresses, dancers, and singers: their roles were directly related to the ideology and self-chosen image of the Tashkent Film Festival and were limited to that of cultural ambassadors of Soviet socialist ideals.[8] Soviet films shown to international guests in Tashkent were intended to strengthen identification with socialist values as well as growing anti-colonial sentiments in African, Asian, and Latin American nations, by promoting the Soviets’ handling of the ‘woman question’. A film like Veil (Паранджа, Parandzha), by Uzbek director Malik Kaiumov screened 1978 in Tashkent, is exemplary in this respect. Officially categorized as a ‘documentary’, the five-minute short film shows black-and-white archival footage of protest marches and mass public burning of veils during Hujum, alongside bodies of women who experienced the full brutality of the campaign’s aftermath. These harrowing images are juxtaposed with cheerful and colorful scenes of modern Uzbek women in the city, accompanied by a gentle and joyous soundscape. A binary narrative is clearly conveyed through the montage—between then and now, between the horrors of the past and the propagated happiness of Uzbek women later in the Soviet period.[9]

.jpg)

Film still,Veil (1978) by Malik Kaiumov (original title: Паранджа, Parandzha). Source: ok.ruvideo/961015646884

One scene in the film stands out, however, in which a teacher is seen with a group of female students in front of a life-size monument of a woman removing her veil. The teacher is shown most probably recounting the story, well-known during Soviet times, of Nurkhon Yuldashkhojayeva, a young dancer who dared to dance on stage without a veil and was killed by her brother in revenge. The Soviets erected a monument to her as a martyr in her hometown of Margilan (in southern Uzbekistan) afterwards, but when the population’s affiliation to Islam was given more recognition again after independence, the monument was removed, as it was deemed incompatible with the new state ideology.[10] In fact, Uzbekistan has experienced increasing popularity of the hijab since the dissolution of the USSR and the overall situation is similar in the neighboring Central Asian countries. But while religion became more present in the public sphere, there are also fears of it becoming too influential in society, as reflected in current debates on clothing policy in the region. Conflicts surrounding the veil underline the inner turmoil over questions concerning identity still present in Central Asia, even three decades after gaining independence. While this analysis does not intend to assess the act of (un)veiling, it seeks to illustrate the extent to which the forced Hujum campaign, as well as its (cinematic) representation, has shaped and continues to shape the role of women in Central Asian society to this day. Women still are among the most vulnerable in Central Asia’s current and male-dominated symbolic politics, yet too often silenced in this debate.

[1] Nicolas Butylin, „Tadschikistan: Warum Frauen im muslimisch geprägten Land kein Kopftuch mehr tragen dürfen”, Berliner Zeitung, June 25, 2024, https://www.berliner-zeitung.de/politik-gesellschaft/geopolitik/tadschikistan-warum-duerfen-frauen-im-muslimisch-gepraegten-land-kein-kopftuch-mehr-tragen-li.2228347

[2] Khalid Adeeb, Central Asia: A New History from the Imperial Conquests to the Present, 1st ed (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021), 215–216.

[3] Marianne Kamp, The New Woman in Uzbekistan: Islam, Modernity, and Unveiling under Communism (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006), 186.

[4] Kamp, The New Woman in Uzbekistan, 32–34.

[5] Adrienne Edgar, “Bolshevism, Patriarchy and the Nation: The Soviet ‘Emancipation’ of Muslim Women in Pan-Islamic Perspective,” Slavic Review 65, no. 2 (2006): 252–264.

[6] Kristen R. Ghodsee, „Die roten Großmütter der Frauenbewegung,“ Le Monde diplomatique, July 8, 2021, https://monde-diplomatique.de/artikel/!5783386.

[7] Masha Salazkina, World Socialist Cinema (Oakland: University of California Press, 2023), 144.

[8] Salazkina, World Socialist Cinema, 154–155.

[9] Salazkina, World Socialist Cinema, 143.

[10] Kamp, The New Woman in Uzbekistan, 205–206.