We are bathed in blue sun rays, two Nigerian girls, one American and one German, gleaming with smiles as we flip through Grace Wales Bonner’s sublime reflections in ‘Rhapsody in the Street’, her curatorial project for A Magazine Curated By. Blues reflect on our cheeks, soaking our hair, drenching supple skin in splendid rays of altered cosmic sunshine.

The archive made me anew.

It taught me how to keep relations alive,

insisted that I learn how to feel my way

Alongside various presences.[1]

—Adjoa Armah, ‘On Living with Archives’

Deep in the blue-black abyss,[2] critical scholars reckon with the experience that is seeped in Black. Sylvia Wynter, Jamaican philosopher, cultural theorist, and writer, points to invention, to material production through counter-imagination,[3] as a necessary and foundational practice of resistance as it allows for the critique of dominant imperial ways of knowing, reviving knowledges from non-European traditions that have been historically de-humanized, erased, and disregarded. Wynter argues that in order to re-envision humanism, and move towards ontological sovereignty, we must consider other narratives, ‘re-enchanting’ discourses and narratives in order to resist resignation and self-negation. Such counter moves reside deep within the liminal, composing and re-composing history, culture, and identity. Wynter not only critiques and upends, but also critically urges towards an embrace of subjectivity and locality.

Considering how such a poetic practice of counter-imaginary and counter-discourse finds expression, one could look to the work of British fashion designer Grace Wales Bonner. London-born, and a graduate of Central Saint Martins, her work unsettles race and gender through a creolizing of British and Jamaican heritage, drawing expansively on the Black Diaspora and its archives. Wales Bonner intimately transforms fixed assumptions on identity, resisting nationalistic postulations through an entangling of myriad cultures, persisting beyond binaries.

Imagined in three acts, the three collections in Wales Bonner’s trilogy, Lovers Rock, Essence, and Black Sunlight, are considered through the lens of musicality, sensuality, and agency through fashioning. Wales Bonner mines and co-creates the archive of the Black diaspora—multiple, scattered, gorgeous, and unwavering—challenging stereotypes through garment and art-making.

Harley Weir, adidas Originals & Wales Bonner, Autumn Winter 2020. Photo: London, 2020. Courtesy: Adidas

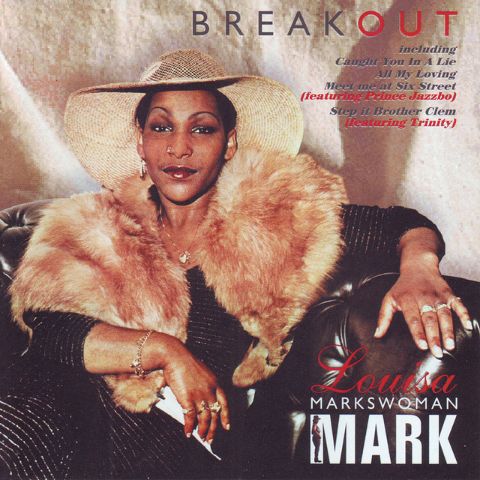

Louisa 'Markswoman' Mark, Breakout, album cover, 1981

ACT I Patois Dreams

On Lovers Rock & Underground Blues

Autumn / Winter 2020

I can still see the track jacket she would wear beneath her father’s military coat; the embroidered epaulets; the afro shaped like a nimbus; the steel toed boots; the clip of a folding knife in the back pocket of her jeans.[4]

—Mahfuz Sultan, Lovers Rock

A coastal scene clothed in balmy lights of dozy afternoon hues. Amid the languor of the maritime space, its cerulean skies, glistening waters, and barren shores, we observe Black bodies in states of physical exertion. Slow-paced bodily movements of stretching and juggling a football approximate the sultry and dreamy atmosphere of the surroundings. In this visual expression of bodies in motion, the frames exude a rhythmic, almost dancelike sublimation of masculine physicality. This piece of visual and aural poetry by the French-Caribbean twin brothers Jalan and Jibril Durimel introduces the first adidas Originals by Wales Bonner collection for Autumn Winter 2020, adjoining the fashion house's main collection titled Lovers Rock. It pays tribute to the underground blues parties of the 1970s and 80s in London and the distinctive sartorial style that characterized them. By merging elements of dress from the Caribbean and insouciant elements of sportswear with traditional British tailoring, Lovers Rock embodies a distinct eclecticism. Imagine football jerseys and tracksuits in Persian green, ivory, and crimson aligning with double-breasted blazers, donkey jackets, and hand-knit beanies.

Wales Bonner’s collection for Lovers Rock skilfully draws on John Goto’s tender 1977 portraits of young British African-Caribbeans at the Lewisham Youth Centre in South London, where he taught evening classes in photography. Encased in black colour fields, the photographs depict regulars who often attended the Lovers Rock night at the centre. Their way of dressing is of particular interest for Grace Wales Bonner and circles back to the confluence of Caribbean and British elements. She reflects: ‘I was interested in how sportswear was naturally integrated into people’s wardrobes alongside tailoring and wanted to speak to this effortless and elevated approach to dressing’.[5] Wales Bonner’s Lovers Rock thus echoes an aesthetic precedent growing out of South London’s underground scene in the mid-seventies dressed in 'Adidas freizeit in hues of crimson, ochre and emerald green'.[6]

Lovers Rock is a style of reggae tinged with sensual bliss and romantic tenderness that originated among the children of Black West Indies immigrants to Britain in the 1970s and 1980s. It is a genre whose sound is shaped by young people falling in and out of love. Mellow rhythms speak of dreamily erotic encounters, scintillating lust, and ephemeral joy. The Black British youth came together in rented flats to dance to Lovers Rock; a sheaf of bodies moving through small rooms, embers of longing rocking bodies back and forth. Carnal communication through ravenously, exhaustingly, sensual bodily articulations. Flailing limbs, gyrating pelvises, and heaving chests. Sweltering heat, throbbing speakers, bodies grinding against each other, and the smell of Ackee and Saltfish, Plantain and Curry Goat all contribute to the hazy atmosphere the tunes instil. The house parties allowed these youth to carve out a space of their own, unencumbered by the discriminatory politics of white British club culture. Moreover, the gatherings provided a sort of sanctuary and respite from the sombre perils that festered beyond the walls, from the tacit and overt reminders of racial adversity and probing injustices lurking outside.

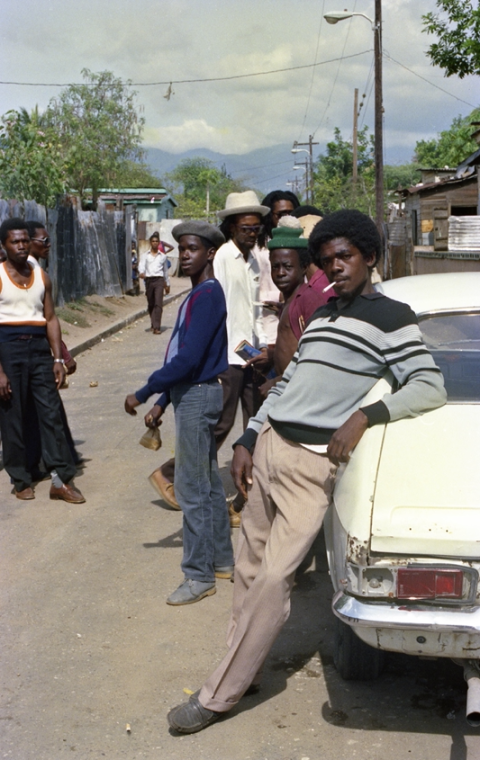

Black British life in the dour 1970s and 80s was suffused with oppressive racism, prejudice, widening income inequality, and police violence. In the fascist-resurgent Britain of that time, the children of the Windrush generation[7] had to endure constant bouts of racism while going about their everyday lives. Numerous reggae-classic songs of that time are imbued with references to this hostile environment. Take Linton Kwesi Johnson’s Inglan Is A Bitch from 1980, in which he proclaims: ‘Inglan is a bitch / dere’s no escapin it / Inglan is a bitch / y’u haffi know how fi suvvive in it’. Curiously, another track merges the harrowing experience of social upheaval—this time in Jamaica—with elements of physical activity and sportswear. Jogging, a classic reggae track by Jamaican Freddie McGregor observes ‘people preparing themselves (for Armageddon)’ as they are ‘keeping fit (fit for the fire)’ while ‘wearing Adidas’. Playing on this idea of armouring up and preparing for the bouts of racism, Ashley Clark, a writer and film programmer from London, discerns a ‘culture of style, substance, resistance. Looking sharp, sharpening up, and keeping fit for the fire’[8] to be found in Wales Bonner’s designs.

Lingering with these rhythmic reverberations produces certain insights when thinking through Wales Bonner’s Lovers Rock. In lieu of working through how rhythm is embodied and passed on physically, her aesthetic practice is concerned with how rhythm can be inscribed into vestimentary forms. Drawing on the concept of ‘rhythmized textiles’ limned in Robert Farris Thompson’s Flash of the Spirit, Bonner states: “I’ve been really interested in rhythmicality and how it manifests as aesthetics, because I find it quite a difficult thing to express visually”.[9] The leitmotif of Lovers Rock can therefore be identified in the mimetic patterns that relate the genre-specific modes of musical production to the art of clothes making. With Lovers Rock, both the formation of textile and sonic images manifest the creative dynamics of creolization processes. Creolization refers to the continuous cultural contact, mixing and mutual transformation of different cultures, and stands in the historical context of the torturous Middle Passage and the enslavement of black people on colonial plantations. Accordingly, the concept counters the principle of unambiguity with a multi-layered and differentiated narrative of the Caribbean and the diaspora.

The garments and looks that structure Lovers Rock hold evident traces of creolization, echoed in features that also relate to the idea of rhythmized textiles—sampling, mixing, and repetition. Sampling refers to the rhythmic amassings of eclectic components, combining various distinct elements into new configurations. Innovation then arises from the way these components are integrated into a cohesive whole. In one of the Lovers Rock looks, Adidas track pants and sneakers go alongside a buttoned wool coat, a roll-neck top worn underneath a striped shirt, and a flat cap. Wales Bonner describes this recitative organizing of tropes of British wardrobe side-by-side sportswear as countering preconceived notions of dressing.

The amalgamation of these disparate elements, at its core, mixing. Wales Bonner builds complex structures where British and Caribbean elements are not only assembled but merged to form one. The before-mentioned Adidas sneaker is embellished with delicate lace stitching and the tracksuits are dyed in colours that are visual reminders of the Caribbean. Lastly, one can observe reiterations of the same motifs throughout and beyond the collection as a whole, forming what Édouard Glissant calls a ‘reconstituted echo or a spiral retelling’.[10] Different interpretations of the Adidas Samba sneaker can also be found in various collections, adding to rhythmic complexity where elements multiply and proliferate as they are reiterated.

Jeano Edwards, adidas Originals & Wales Bonner Spring Summer 2021. Photo: Portmore, Jamaica, 2021. Courtesy: Adidas

Beth Lesser, Volcano Corner CocoaTea, 1984, courtesy die Künstlerin

ACT II Sundrenched Tremblings

On Essence & Dancehall

Spring / Summer 2021

The archive demanded a fuller relationship with the land & the people inhabiting it.[11]

Bells chime against azure waves, washing over one another, in ease. Kingston soundscapes glimmer, glittering with sparkling sunlight. Di sun set, and it’s the most beautiful place to be.[12] Tranquil waters wash over beautiful, deep skin, bathing salty ocean breeze over mind and heart. Effortlessly, evening arrives with its seductive atomic chroma of emerald greens, golds, reds: vibrant hibiscus, bougainvillea, and ancient Mahogany, with its subtle floral fragrance. Saccharine Night-Blooming Jasmine ablute, cascading warmth as night approaches.

Gasoline plumes the fragrant air, regal lapels and double-breasted cloak press against flowing wind, sporty and militant, a young man makes his way home. Lush greens envelope, consume, swaying with the last glimmers of sun, oscillating between light and dark, warming aroma and calling us home. Jeano Edwards’s film Thinkin Home embalms the intonations of multiple perspectives of Essence, recording the movement of six men going home in Jamaica, recalling the raw realism of the 1972 movie The Harder They Come.

Wales Bonner’s Essence, the second collection of the triptych, relays memories of the early eighties, at the height of dancehall in Kingston, Jamaica, reflecting and thinking with self-fashioning tendencies of reggae icons like Augustus Pablo’s quotidian wear; the poetic musings by author Marlon James; and intimate capture by photographer Beth Lesser. The collection pays graceful homage to Dancehall queens from Kingston, crafting western wear from a soft Black gaze, strolling fluidly through the evening sun.

Speaking of Rastafarians in Jamaica, Stuart Hall emphasizes Caribbean culture as transformation, stating ‘They became what they are. [...] And in so doing, they did not assume that their cultural resources lay in the past.’[13] Inventing new beginnings and languages, reggae sounds were a critical medium for the expression of these beliefs and realities. The Rasta movement originated in the thirties while reggae emerged in the sixties, influenced by older genres like Jamaican ska and American Blues. Augustus Pablo, born Horace Swaby, was an eminent Jamaican roots reggae musician, whose typical fashioning including something like a knit tam Rastafarian cap atop lush locks, and a simple loose-fitted button-down shirt. Simple and laid-back, his look exuded comfort, sitting back coolly in cotton trousers. This fashioning was typical of reggae musicians, highlighting the relaxed aesthetic and the embrace of movement in the scene. An understated elegance, such attire projects an image of grounded and rooted connection to Rastafarian culture and spirituality, and a dedication to reggae.[14]

Dancehall has roots deeply grounded in the socio-cultural fabric of Jamaica, originating in the late seventies and evolving from reggae music. Its sound emphasizes bass and rhythm as a result of the shift in technology and in turn the production of digital music because of increased accessibility of instruments such as the Casio MT-40 keyboard. Birthing ‘riddim’ and revolutionizing dancehall music and culture, as photographed by Beth Lesser, a key reference for Wales Bonner. Dancehall continues to evolve with technology, and with it fashioning, identity, and movement, allowing for voices to resist oppression and express agency.

‘If hip-hop’s visual language is graffiti, then dancehall’s visual language is the sign, the event poster—’t eh notice that big t’ings a gwaan down di street’, writes Marlon James in Serious Tings a Go. In ‘Dancehall Queens Past Present Future’, Akeem Smith contributes to the memory and archive of Dancehall through imaging and storytelling, sharing and connecting to kinship and cultural lineage through conversation and found video, disseminated through imaged stills of digitized family photos. A display of ‘creativity’ and ‘expression’,[15] Dancehall fashioning was all about the party, the scene, and showing out. The clothing is everyday, cool, easeful, yet with a thoughtful sensibility.

Sublime, kinky hair soaks up the ambience of ease. Intentional strides, straight postures, and long limbs stroll along cyanic walls, flattened earth under worn Sambas. The matching tracksuit reverberates landscape, echoing the Blue Mahoe’s explosions of purple-blues.[16] Trackpants, loosely structured, flow and sway. Young Black eyes, cool, determined, and gleaming. As much of Wales Bonner’s practice does, Essence highlights a soft Black masculinity, a counter-discourse to the violent stereotyping of the Black man or boy, highlighting characters embodying joy, unhurriedly content and grounded, steeped in bliss. The colours of the garments, jersey and otherwise carry hues of the Jamaican landscape, creolized with military wear of Jamaican aesthetic heritage or traditional British tailoring, over nationalistic signifiers and singular codes, bending expectation on the representations of both gender and race.

Tyler Mitchell, adidas Originals by Wales Bonner Autumn Winter 2021. Photo: London, 2021. Courtesy: Adidas

ACT III Black Oxford

On Black Sunlight & Black Intellectualism

Autumn / Winter 2021

In the mute roar of autumn, in the shrill

treble of the aspens, the basso of the holm-oaks,

in the silvery wandering aria of the Schuylkill,

the poplars choiring with a quillion strokes,

find love for what is not your land, a blazing country

in eastern Pennsylvania with the DVD going

in the rented burgundy Jeep […].[17]

– Derek Walcott, Pastoral

School is out. Late summer sun blanketing Black boys at play in sylvan surroundings of rural idyll. A patch of meadow almost entirely crusted with burnt grass encased in billowing woodland constitutes the environment in which the children run around, ride bikes and play soccer. Photographer Tyler Mitchell compacts and meshes these scenes of Black leisure and levity into patterned visuals of the countryside as a space of refuge and repose. Pastoral interludes at the hem of reality drenched in a warm and fuzzy atmosphere. A delicately crafted visual realm of tranquillity in which blooms of juvenile innocence and joy are central. For the last iteration of the Caribbean trilogy, Adidas and Wales Bonner partnered up with Tyler Mitchell to present their Autumn Winter 2021 collection accompanying the house’s main collection titled Black Sunlight.

Cultivated in Black academia and intellectualism, Black Sunlight takes inspiration from the postcolonial discourse of Black thinkers, scholars and poets. Extending the research practice to literature, the writing of Saint Lucian poet and playwright Derek Walcott meanders through the collection serving as a salient reference point. In Pastoral, Walcott at once evokes and complicates pastoral motives of American nature as he pries apart the seemingly cohesive and idyllic meaning embedded in the landscape and re-inscribes the erased histories of violence, displacement, and exploitation.

Mitchell’s oeuvre is structured by images that urge to create a visual world of ‘beauty, style, utopia, and the landscape that expands visions of Black life and embraces the extraordinary radiance of the everyday’.[18] Gentle musings on the countryside as a site of leisure and community give shape to one of the chapters titled Postcolonial/Pastoral as part of his first solo exhibition in Germany at C/O Berlin. Complementing this motif, the campaign featuring collegiate leisurewear illustrates counter-imaginings of a Black Pastoral and Black leisure. The visual narrative resurrects the pastoral not to venerate the countryside as earthen sublimity but to challenge the notion of the pastoral with its tenuous and contorted recordings of Black presence. In poetry as much as in art, the pastoral was determined by and limited to the depiction of white solace-seeking individuals escaping the vices of the urban. Text and image alike materialized an imaginary landscape of the virtues of the rural—its perceived serenity, quietude, and profusion. Wales Bonner’s reimagining of contemporary Black life beyond prescribed urbanity centres Black people pursuing recreational activities in a bucolic landscape. The counter-narrative potency of these images centres the pastoral as a site of Black rest, leisure and sensuality.

Conclusion

There is more to the archive than you may see.[19]

—Adjoa Armah, ‘On Living with Archives’

Wales Bonner is both a fashion house and a passionate research project,[20] forming multiple inventions through a deep regard for reality and beauty. In her triad with Adidas, Wales Bonner’s refined crafting of the convergence of Caribbean and British through Lovers Rock, Essence, and Black Oxford resists racial and gendered tropes, counter-imagining through garments, forming a space where agency and exuberant expression, intimacy with landscape and its cultural embrace, and a softer masculinity coexist Wales Bonner’s grounds her work in research practice and Black intellectual thought, which she sees as an artistic and spiritual endeavour that includes the study of literature, sound, movement, and photography. Bringing in narrative, rather than forming a narrative of being outside, Grace Wales Bonner brings cultural perspectives into the fashion landscape, narratives which she did not see in that landscape, yet were so familiar to her in her own life. The practice brings people in the world to expand on that research outcome, together, „collaborative expansion,” and disruptively proliferate a refined image of Black representation.[21]

[1] Adjoa Armah, ‘On Living with Archives’, A Magazine Curated By, Grace Wales Bonner, Rhapsody in the Street (2021), 76.

[2] Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 8.

[3] Frantz Fanon, ‘Introduction’, in Black Skins, White Masks, tr. Charles Lam Markmann (London: Pluto Press, 1986).

[4] Mahfuz Sultan, ‘Lovers Rock’, Reflections on Essence, 2020, 6.

[5] Ted Stansfield, ‘Grace Wales Bonner on Her Standout Adidas Collaboration’, AnOther Magazine (2 December 2020), https://www.anothermag.com/fashion-beauty/12985/grace-wales-bonner-on-her-standout-adidas-collaboration.

[6] Wales Bonner, ‘Lovers Rock’, https://walesbonner.com/pages/lovers-rock.

[7] The term Windrush Generation for many years referred to the African-Caribbeans—or West Indians, as we were called then—who arrived at London’s Tilbury Docks in June 1948. The term has since been redefined to encapsulate those who arrived throughout the latter half of the twentieth century.

[8] Ashley Clark, ‘Present and Correct: Adidas and Wales Bonner FW20, Ashley Clark on the Lineage of Resistance in British Caribbean Culture’, Ssense (1 December 2020), https://www.ssense.com/en-gb/editorial/fashion/present-and-correct-adidas-and-wales-bonner-fw20.

[9] Claire Marie Healy, ‘Grace Wales Bonner’, Dazed (15 September 2020), https://www.dazeddigital.com/read-up-act-up-autumn-2020/article/50399/1/read-up-act-up-autumn-2020-grace-wales-bonner-guest-edit.

[10] Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, tr. Betsy Wing, (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2010), 16.

[11] Armah, ‘On Living with Archives’, 82.

[12] Jeano Edwards, Thinkin Home [video], Wales Bonner, 2020, 5' 25", https://walesbonner.com/pages/thinkin-home.

[13] Stuart Hall, Cultural Studies 1983: A Theoretical History (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 144.

[14] Wales Bonner, Essence, https://walesbonner.com/pages/essence.

[15] Akeem Smith, ‘Dancehall Queens’, A Magazine Curated By, Grace Wales Bonner, Rhapsody in the Street (2021), 168.

[16] Edwards,‘Thinking Home’, 1' 33".

[17] Derek Walcott, White Egrets (London: Faber and Faber, 2010), 43.

[18]C/O Berlin, ‘Press Release: Tyler Mitchell, Wish This Was Real’ (April 2024), https://co-berlin.org/sites/default/files/2024-06/CO%20Berlin_Press%20Kit_Tyler%20Mitchell_Wish%20This%20Was%20Real_EN.pdf.

[19] Adjoa Armah, ‘On Living with Archives’, A Magazine Curated By, Grace Wales Bonner, Rhapsody in the Street (2021), 76.

[20] Frantz Fanon, ‘On National Culture’, in The Wretched of the Earth, tr. Constance Farrington (New York: Grove Press, 1963), 206.

[21] Cédric Fauq, Christelle Oyiri, Sumayya Vally, Grace Wales Bonner, ‘Conversations | Pan-Africanism and Contemporary Aesthetics’, 24' 20”.