The exhibition Echoes of the Brother Countries. What is the Price of Memory and What is the Cost of Amnesia? Or Visions and Illusions of Anti-Imperialist Solidarities at HKW, which took place in 2024, situated us within the realm of the forgotten or unrecognized stories of the ‘brother countries’, particularly with regard to the international socialist alliances formed between the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and other socialist and socialist-leaning postcolonial countries between 1949 and 1990. Agreements between the GDR and Angola, Cuba, Mozambique, and Vietnam during that period led to significant migration of contract workers and student exchanges. The GDR also entered into further agreements on a lesser scale during the Cold War, including with Cambodia, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Ghana, and granted asylum to political refugees from Chile, Iran, and Turkey, among others, enhancing the avenues through which thousands migrated to the GDR. Echoes of the Brother Countries addressed the complex histories of solidarity and migration that shaped GDR communities and their repercussions until today. Against nationalistic narratives, the following text by Sarnt Utamachote on the life and work of the Cambodian sculptor Songhak Ky, who migrated to the GDR in 1972, continues HKW’s engagement with intergenerational and transnational narratives and their related artistic practices and aesthetic languages, contributing to an urgent expansion of social literacy on the migrant histories that have shaped and continue to shape Germany’s diverse society.

—Paz Guevara, Curator (Exhibition Practices), HKW

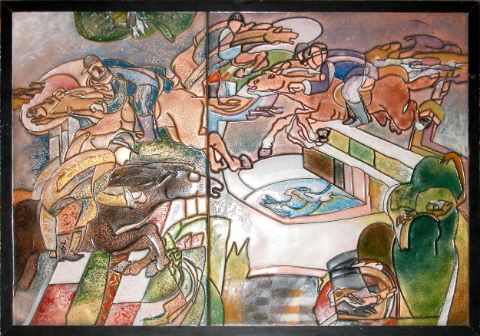

Original photograph of Songhak Ky’s work Begegnung [encounter, 1995]. Courtesy Constanze Pressehaus/Ralf Frank Hartman. Photo: Udo Mölzer

The author and Linda Ky, Songhak’s daughter with her father’s work in the exhibition Echoes of the Brother Countries, HKW, 2024. Courtesy Sarnt Utamachote

Songhak Ky[1] (b. 1950, Kandal–d. 2000, Berlin) was a Cambodian artist who came to study art and design (metal and enamel work) in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in 1972. He subsequently fled to the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) in 1987 and remained without returning to Cambodia until his death in 2000 in exile. This text aims firstly to shed light on and historicize one of many examples of the artistic practice of migrants in the GDR, whose presence has rarely been researched, and secondly, to link Ky’s artistic positions to a larger socialist internationalist context, in contrast to an attempt to read a notion of nationalism onto them. For many artists of Cambodian origin, regardless if they were to be categorized as ‘contemporary’ or ‘modern’ (let alone if either word has any functional translation in Khmer), readings of their works tend to refer to and define them under two paradigms. One is trauma, specifically in relation to the Khmer Rouge’s genocide (1975–1979) and Cambodia’s long period of civil wars (1967–1975). The second angle is one of craft and tradition, and the tendency to assign ‘Cambodianness’ (or even a broader ‘Asianness’) to the artworks regardless of how they have been made. It could be argued that this need to ‘perform’ a particular mix of exoticism and authenticity lingers on for all migrants in the West until now. In the specific case of Cambodia, the genocide and civil wars have created a gap in its official art history, rendering those who live (and survive) in diaspora a living archive, irrespective of if they want to be associated with the nation-state now called Cambodia or not; the latter was the case with Ky. This text aims to shift away from these two discourses and look at Ky’s work in a larger international context as well as on a local scale.

I came across the existence of Ky’s works through the circuitous route of artistic research, so I write neither from the position of a historian nor as an expert on Cambodian art or the art history of the GDR. In the context of archival research for ‘Where is my karaoke? And still we sing’ (2022), a research and exhibition project co-curated in collaboration with art historian Phuong Phan, we came across Ky’s name in the archive of Berlin’s Akademie der Künste in 2021. This led us to the archive of the Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle [Burg Giebichenstein University of Art and Design], formerly called the Hochschule für Industrielle Formgestaltung [Academy of Industrial Design] Burg-Giebichenstein Halle an der Saale, where Ky studied in the 1970s, and ultimately to exhibiting his project Element für eine Fassadengestaltung [element for a facade decoration, 1974–75] at the D21 Project Space in Leipzig. In the same room, I commissioned the Postmigrant Radio[2] collective based in Leipzig to create a piece on Cambodian voices in the GDR, resulting in an installation called Identity [អត្តសញ្ញាណ].[3] It was through talking to a Cambodian visitor to the exhibition that I learned of Ky’s daughter Linda and her mother Annerose and was later able to meet and get to know them. Through those exchanges, I found many more documents, photographs, and Ky’s sculptures in Annerose’s home. One of them, a piece called Begegnung [encounter] from 1995, was shown in the Echoes of the Brother Countries exhibition at HKW in 2024, for which I collaborated on research. This text departs from the aforementioned experiences, as a written space for further research and reflection, and is dedicated to Ky and his artistic legacy.

Postmigrant Radio collective, Identity [ត្តសញ្ញាណ], 2022, installation view, D21 Project Space, Leipzig. Photo: Postmigrant Radio

Historical Entanglements

It’s not easy to summarize the history of the bilateral relations between the GDR and Cambodia, since both nations have an extremely complicated historiography to begin with. It was after 1969 that Cambodia sent delegates to meet GDR First Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party (SED) Walter Ulbricht. Subsequently Heinz-Dieter Winter was assigned as the first ambassador of the GDR to Phnom Penh. This led to the end of its diplomatic ties with the FRG.[4] Cambodian students, including Ky, arrived in the GDR from this period onwards, and continued to do so until 1975. Even after Lon Nol’s coup in 1970, the GDR ambassador stayed in Phnom Penh and kept its relations open.[5] Between 1975 and 1979, the Khmer Rouge showed no interest in establishing proper diplomatic ties with the GDR. Its embassy in (East) Berlin closed down in 1977. In 1979 after the ‘Vietnamese takeover’, binational ties were re-established, now between the GDR and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea, with the GDR and Vietnam being among the first nation-states who recognized the government of Pen Sovann (who came to the GDR on a diplomatic visit that same year ).[6] Many more Cambodians went on to study in the Eastern bloc during the 1980s. The relationship continued towards 1989 and declined further in the wake of unification. Later, when King Norodom Sihanouk was called to return as constitutional monarch and the Kingdom of Cambodia was reestablished in 1993,[7] it marked the end of socialist-leaning Cambodia. The GDR of course ceased to exist earlier, when it officially unified with the FRG on 3 October 1990. One can see here how the history of socialist internationalism is not a linear one, but very fluid and complicated. In the post-unification period, many Cambodians (as well as others who had come to the GDR from various ‘Third World’ countries) remained here and their artistic works remained untouched, yet at the same time, they seemingly faded into a lost archive of a state which no longer existed. Many did not return to their countries of origin, including Ky.

It seems that international students coming to the GDR were encouraged to perform their ‘world cultures’, when aligned with socialist ideals. As an example, in the 1960s Norodom Sihanouk (who, at various points served as Cambodia’s king, head of state, and prime minister) came up with the idea of establishing cultural diplomacy between the two countries. He recorded his musical compositions on the LP Palmen am Meer: Tanzmusik aus Kambodscha [Palm trees by the sea: Dance music from Cambodia, 1968] with the Leipzig Dance Orchestra; it was released on the GDR’s official label, Amiga. One can easily spot the ‘West meets East’ attempt in these songs. A similar approach can be found in the band Bayon, whose band member Sonny Thet (1954–) was one of the chosen students who were sent to study in the West (in his case, western classical music and cello at the College of Music Franz Liszt in Weimar in 1968).[8] Bayon went on tour extensively in the Eastern bloc, including in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, and Romania and found success amongst young audiences, under the banner of what people might have later called ‘world music’.

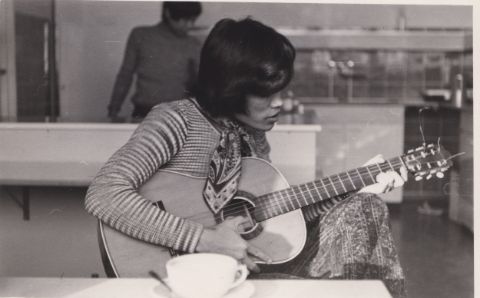

Songhak Ky with guitar, 1970s, in the Academy of Industrial Design, Halle. Courtesy: Vann Tay Bean

Songhak Ky During His Studies in the GDR

This photograph of Ky holding a guitar in a sarong was given to me by Vann Tay Bean, who took it. Bean came to study in the GDR earlier than Ky (1966 to Leipzig, and from 1967–1972 in the ceramics faculty at the same Academy of Industrial Design in Halle where Ky studied). This photo surprised Ky’s family, because, according to them, he never really owned a guitar, nor had any musical ability. In fact, they told me that his singing skills were so bad that they ended up not liking the Khmer music he loved listening to. At this point, I’m reminded that there is something much more than meets the eye when looking at the archive and undertaking artistic research in this mode. Rather than romanticizing that he was a great musician, we can reflect on how Ky ‘performs’—now across time—for those who look at him, to see perhaps what he was not.

After receiving a place to study art in the GDR city Halle an der Saale Ky gave up his architecture studies in Phnom Penh[9]—an interest which one would recognize later—and arrived in Leipzig at the Herder Institute in 1971, to first attend German language and integration classes. One year later, he enrolled in the metal and enamel faculty at the Hochschule für Industrielle Formgestaltung [Academy of Industrial Design] Burg-Giebichenstein, in Halle (Saale), under Prof. Irmtraud Ohme (1937–2002). Due to political instability in Cambodia, he prolonged his studies and then worked as Ohme’s assistant until 1980 (as long as he had a working contract, the GDR state would not deport him). His stay in the GDR had to be extended continuously every year, a burden which he had to suffer until 1990, at which time he was granted German citizenship from the FRG shortly before unification. In 1980—as the Khmer Rouge regime came to an end—he decided to start his freelance career and had his first official exhibition as an artist in the Bezirkskunstausstellung in Halle. Around the same time, he received news from his sister about the Khmer Rouge’s genocide, as well as the fact that his uncle had been sent to a re-education camp and never made out it alive.

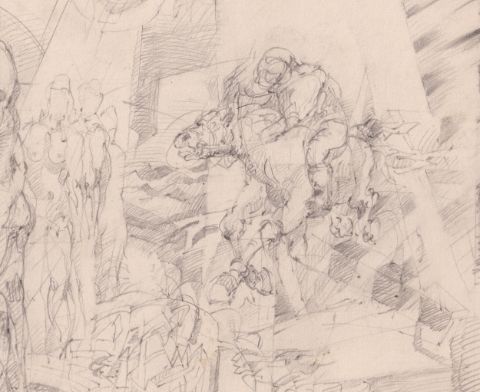

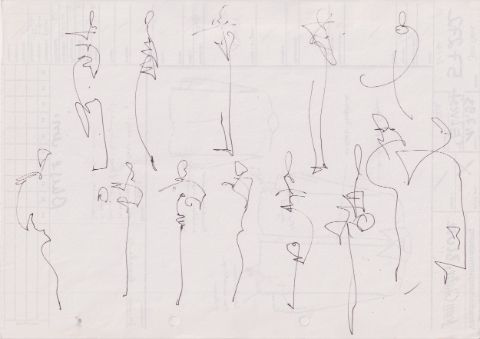

Songhak Ky, sketch of horse rider, as a part of a larger page of figurative sketches. Courtesy of Annerose Ky. Photo: Sarnt Utamachote

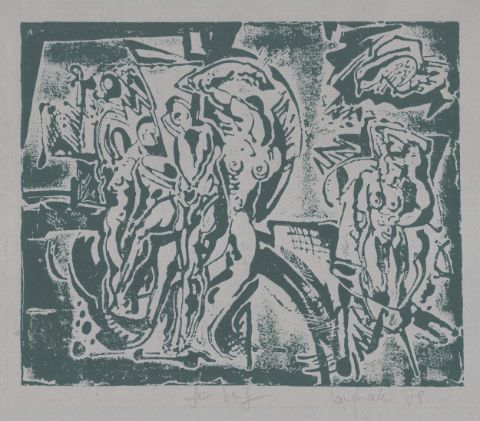

Songhak Ky, Reiter [rider], 1977, enamel work, 55 × 75 cm, Burg Sammlung, Z 3.2d,1. © Archiv und Sammlung Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle

Ky met Annerose, who became his wife and the mother of Linda Ky, in 1973 and they lived together in a small Plattenbau apartment on Straße der Waffenbrüderschaft in Halle. The flat was provided by the Wohnungsamt, with relatively affordable, state-subsidized rent, as was characteristic at the time. They survived on limited means, cooking many dishes with GDR-provided ‘Eastern’ short grain rice (Ost-Milchreis) and canned peanuts, with rare access to Asian spices. Ky and his wife listened to Tina Turner and Bruce Springsteen, only had access to the channel ARD from the West, beyond the GDR’s state-regulated offerings. Often, he would disappear for six weeks at a stretch to produce new works, which left daughter Linda under the sole care of Annerose. He would barely explain to them what his sculptures meant, simply always calling them ‘work’ and operating with a clear division between his private life and his public life as an artist.[10] When drawing paper was scarce, he repurposed his wife’s sewing patterns and sketched his ideas on the reverse side. He also tried to teach his daughter to draw human figures, but failed to hold her interest.

After becoming a member of the GDR Association of Visual Arts [Verband bildender Künstler der DDR, VBKD] in 1981, Ky was granted access to materials such as various metals, which were otherwise strictly rationed due to limited supply. He used them to produce works for a few exhibitions, especially via the format of ‘symposia’ (where artists would gather to make new works). He produced more full-colour enamel works during the era of being associated with Burg-Giebichenstein, as this form of sculpture required a kiln system in the studio, which was not easy to find in other non-institutional ateliers. A few state-sponsored shows featured his early works, such as Metallgestaltung in der DDR [Metal design in the GDR] at the State Gallery Moritzburg (now Kunstmuseum Moritzburg Halle) in 1981 and again in a Part 2 in 1986; the 9th and 10th Kunstausstellung der DDR [Art showcase of the GDR, 1982–3/1987–88, various locations, Dresden]; and Junge Künstler der DDR [Young artists of the GDR] at Altes Museum in East Berlin in 1981 and 1984. In the south part of city park Glacis in Magdeburg, one can still see his public piece Lebensraum [living space, 1981], which was acquired by the city.[11]

Other students in the GDR are living proof of historical entanglements, having brought their international cultures, artistic references, and techniques and exchanged amongst them. For example, Chan Ley Heng (1931–2011) studied architecture and poster design at the School of Cambodian Arts until 1964. In a not directly related parallel to Songhak and others, he produced abstract paintings, of which the work Saok Niedakamm [សោកនាដកម្ម or The Tragedy, 1974/75] remains ‘perhaps the sole surviving example of an abstract (or strictly speaking, semi-abstract) artwork from Cambodia completed in this period [before Khmer Rouge]’ according to art historian Roger Nelson.[12] Seemingly a study in preparation for a larger piece, it uses flat colours, consistent with the poster design skills he studied. In its use of bold colours and abstracted simplicity, it bears resemblance to Ky’s approach—even though coming from two different backgrounds. One can surmise that these artists were affected by the constant negotiation between two modes: of ‘figurative’ (which, depending on the context, meant ‘not modern’; was linked to nationalism in Asia, exoticism in Europe, sometimes Socialist Realism) and ‘modern’ (meaning: internationalism in Asia, American cosmopolitanism in Europe). Another Cambodian artist associated with GDR is Sam Yoeun (1933–1970),[13] who via his friendship with Lea Grundig (1906–1977), even supported Vann Tay Bean and Eng Seng Thay (1951–) to receive scholarships in the GDR.

On one of Ky’s undated sketches of fluid figures; printing from the sewing pattern he used as drawing paper shows through from the other side. It is possible that this study ultimately resulted in the work Tänzerin [female dancer, 1993]. Courtesy of Annerose Ky. Photo: Sarnt Utamachote

Songhak Ky and Socialist Realism

The notion of contemporary art in the GDR was and is highly contested—not to mention the debates in the broader Eastern bloc region—in constant negotiation with individuals from each era. The principle of ‘socialist realism’ advanced by the Soviet model was based on the idea that art is a functional tool in educating and reflecting on social phenomena. The 1950s ‘formalism debate’ in the early GDR rejected both modernist approaches from the Bauhaus (‘form follows function’) and the ‘international’ style of what the GDR termed ‘American imperialism’,[14] accusing both of stripping away national references and cultural specificities. However, towards the 1960s, the cultural discourse in the GDR shifted to reappraise both Bauhaus principles and functionalism, among other things leading to the creation of cities like Halle-Neustadt (where Ky resided) being designed by architects associated with the Bauhaus, like Richard Paulick.[15]

Anette Schwarz, an art historian, has referred to Ky’s work as ‘anthropomorphic sculpture’.[16] I also found early influences on Ky’s work from the Bauhaus, GDR pedagogy, and 1960–80s internationalism. One can track down the Italian style of, for example, Renato Guttuso (1911–1987), ‘whose aesthetic offers complementarity between forms and colours, between the politics of arts and artists; a third way between Stalin’s realism and the modern, with elements from cubism, expressionism, and abstraction’.[17] Even more influential back then was the style of Josep Renau (1907–1982), a Spanish mural artist who moved to the GDR in 1958 and created murals that blended the famous Mexican mural tradition with socialist working-class aesthetics in architecture and arts.[18] His work Einheit der Arbeiterklasse und Gründung der DDR [Unity of the working class and the founding of the GDR] was acquired by the city of Halle in 1974 for the facade of Stadion 5[19]—a piece that definitely inspired Ky as he biked through the city every day. These works in public space served as perfect examples of how to fulfil art’s function in socialist society, and hence were widely accepted in this period.[20] The influences of Mexican muralism already could be seen in a 1957 exhibition that featured non-German works dedicated to Mexikanische Grafik [Mexican Graphic] at the Museum of Visual Art Leipzig, which was a collaboration between the VBKD and the National Front of Plastic Arts Mexico.[21] But in the end, the most obvious figure to directly influence Ky was his professor Irmtraud Ohme, who encouraged many students to explore sculptural languages and forms. This can be seen in publications about Ohme’s work, as she constantly utilized organic forms and distorted them into geometrical large-scale abstractions, mostly found in public space.

%201978.jpg)

Songhak Ky, Untitled (Grafik), 1978, sketch made during his studies, 16.5 × 19.8 cm, Burg Sammlung, Z 6.1, 529. © Archiv und Sammlung Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle

Songhak Ky as a ‘World’ Contemporary Sculptor

Ky later decided to apply for political asylum in the FRG in 1987, yet his application was rejected on the basis that he could not prove that he would encounter possible danger if he were to return to Cambodia. His biography was tainted as well by his refusal to be ‘converted’ by the new People’s Republic of Kampuchea’s embassy, which in the 1980s established a policy of political ‘reschooling’ [Umschulung] for Cambodian students who came to the GDR before 1975 (for fear of them being associated with the Khmer Rouge or Lon Nol’s regime). Ky explicitly stated in his interview at the asylum procedure: “I was not politically active in the GDR, but against my will I regularly received propaganda pamphlets from Cambodia, which were distributed by the Cambodian Embassy.”[22]

Annerose, whose GDR passport was recognized later by the FRG, was able to bring the entire family, i.e. Ky and their daughter Linda, to the FRG under the Family Unification Application [Familienzusammenführungsantrag] in March 1989 (before the fall of the Berlin Wall that November). At that point, Ky’s status as the spouse of a German citizen was recognized, and in November 1990, he received German citizenship. After having to live one year in a refugee camp at Marienfelde (as a GDR citizen), and after years of effort and hardship (‘In the West it was really not comfortable!’),[23] the family finally settled into their own apartment in Berlin Wilmersdorf in 1993, in which Annerose still lives today.

In 1987 Ky joined the Professional Association of Visual Artists (BBK), the western counterpart to the GDR Association of Visual Arts. This is when more available publications of his works can be found, as he intensely produced many more independent works in the 1990s. Further exhibitions included a solo show in 1994 Galerie am Meer in Warnemünde, and group shows in the Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf; Kunst-Dialoge in Karlsruhe; and Galerie Schlassgoart, Luxemburg (all 1994); and in the exhibition Metallplastik, Grassi Museum, Leipzig and Strasbourg, 1995. An extensive catalogue documents one of Ky’s last solo exhibitions, at Constanze Pressehaus in 1996, curated by Ralf Frank Hartmann and Anette Schwartz.

Songhak Ky, Kleines Pfahlwerk [small stilt work, 1995]. Courtesy Constanze Pressehaus/Ralf Frank Hartmann. Photo: Udo Mölzer

The majority of Ky’s works during this era aligned themselves with the words ‘cosmopolitan’ and ‘modern’, as he moved beyond the use of colour and enamel and immersed himself in producing corroded metal constructivist sculptures. One notices that he barely took reference from anything particularly Cambodian, if not ‘Asian’ in this period. This could be read as an almost political stance that he took, as he explicitly distanced himself from his country of birth, indeed never returned nor visited Cambodia again before his death. While we cannot know for certain which artists inspired him, in some of his personal papers (presumably from the 1990s) that I was able to look at, Ky had listed exhibition titles like Politische Konstruktivisten – Die „Progressiven“ 1919–1933 [Political constructivists – the progressives 1919–1933], an exhibition that look place at the Akademie der Künste in (West) Berlin in 1975, and artists like Josef Albers, Michael Austin Dunbar, Alexey Klimov, Henry Moore, etc.—all associated with the languages of abstraction in the US-American avant-garde and public art. I found no mention of any other Cambodian artist in his papers.

However, in his practice, there might be references in Ky’s apparent use of cubist methods in portraying Asian motifs, as seen in the work Kleines Pfahlwerk [small stilt work,1995], which resembles an Asian stilt house flipped on its side.[24] Such stilt houses are common around the Tonlé Sap and Mekong rivers. Or even in the work Begegnung [encounter, 1995), shown in the exhibition Echoes of the Brother Countries at HKW, which Ky described as a fusion between East and West, between Asian figurative craft and western constructivism.[25] Numerous journalists and critics (since the GDR era) referred to Ky as a Weltkünstler [‘world artist’],[26] yet failed in trying to link him with any specific Asian motif, instead remaining general and vague. For example, Ralf Frank Hartmann recalled Ky’s principle of destroying and breaking apart forms, constantly twisting, differentiating the piece’s geometry. He furthermore wrote: “The essence of Asian art, whose ornamental physicality is characterized by reduction and concentration on essential elements, is broken up by the artist constantly shifting from symmetry to asymmetry, bringing ornamental and free-form concepts into discussion with each other, creating a playful contrast between two opposing design principles and thus reflecting cultural differences.”[27]

Songhak Ky (from left to right): Duplex (1995), Balance (1997), and Duo (1995), installation view, DISLOCATIONS—within reach, Kunst Raum Mitte, 2025. Curated by Agnieszka Roguski and Natalie Keppler, with research contribution from the author. Courtesy Kunst Raum Mitte. Photo: Jannis Uffrecht

Songhak Ky in Exile

Had Ky not sought asylum in the West, he would have shared the fate of other students and contract workers after 1989, when, with the dissolution of the GDR state, all contracts or infrastructural agreements associated with the previous regime collapsed, disappeared, or became invalid. Contract workers, especially from Angola, Cuba, Mozambique, and Vietnam, among others, either returned back to their home countries without full payment and various benefits promised in their contracts, or were deported. While some native Germans celebrated the day of unification, many with migrant backgrounds hid themselves in their apartments, fearing for their future. Some of these former socialist housing blocks became the target of arson and violent attacks, as new right-wing terror groups were on the rise.[28]

When Ky shouted ‘I am German now!’ and was happy to have his newly-acquired German passport in November 1990, this feeling was one he shared with generations of migrants in Germany before him: the search for self-assimilation and perhaps even the idea of becoming European. We will never know why Ky never visited Cambodia again for the rest of his life. The fact that he produced so many public sculptures for German cities towards the end of his life shows that he wanted his work to be seen and for his artistic viewpoint to be recognized as (even a decorative) part of the German landscape. All of the things he produced ended up yielding ‘their own logic’ (in Hartmann’s words), which this text starts to unpack. It is possible that within the Cold War artistic debates and his life across the competing blocs that his work was framed, and reframed from socialist realism to abstract art. Perhaps later his work gained a stronger association with international style, in line with a more free-form, modern sculptural language which transcended time, nationality, space, and historicization. The legacy of his works, like many those before him, was subjected to German unification, liberalization of the art markets, and the eradication of GDR histories. Ky passed away in 2000 due to brain cancer. His works have become, via the tides of time, fragments of the incomplete histories of Cambodian contemporary art, socialist internationalism in the GDR, and of post-unification migrant societies.

In the end, because a picture has no tone or music to it, one can never know if Songhak really played that guitar or not. Much like the memories that surround it, Songhak, and every migrant who faced hardship in this part of the world, perform something for us—now it’s time to look and try to hear more closely.[29]

[1] This is how the name appears in German archives and is used in the text; it would be Ky Song Hak according to Khmer naming conventions.

[2] Postmigrant Radio is a Leipzig-based project of Laura Anh Thu Dang and friends, including Elisa Ly.

[3] See https://www.d21-leipzig.de/de/ausstellung/where-is-my-karaoke-still-we-sing/.

[4] Bernd Schäfer, ‘Partnerschaft im Schatten Vietnams: Die DDR und Kambodscha/Kampuchea (1969–1989)’, in Gewalt und Freundschaft: Kambodscha und die DDR im Zeitalter der Ideologien (Weimar: Stiftung Ettersberg, 2021), 16–17.

[5] Schäfer, ‘Partnerschaft im Schatten Vietnams’, 19.

[6] Schäfer, 30–31.

[7] Schäfer, 34.

[8] Interview with Sonny Thet and the author, 2022.

[9] Anette Schwarz, ‘Konstruktion, Konzentration und Konsequenz in der Skulptur’, in Song Hak Ky Skulpturen (Berlin: Constanze Pressehaus, 1996), 10.

[10] Interview with Linda and Annerose Ky and the author, 2024.

[11] See https://www.volksstimme.de/lokal/magdeburg/video-magdeburg-glacis-anlagen-ein-park-zwischen-den-welten-sind-3672980.

[12] Roger Nelson, ‘Modernity and Contemporaneity in “Cambodian Arts” After Independence’, diss. University of Melbourne, 2017, 121.

[13] See https://www.nationalgallery.sg/sg/en/learn-about-art/magazine/sam-yoeuns-etchings-from-the-1960s.html.

[14] Wolfgang Thöner, ‘From an “Alien, Hostile Phenomenon” to the “Poetry of the Future”: On the Bauhaus Reception in East Germany, 1945–70’, GHI Bulletin Supplement 2 (2005): 115–137, here 120.

[15] Thöner, ‘From an “Alien, Hostile Phenomenon” to the “Poetry of the Future”’, 128–29.

[16] Schwarz, ‘Konstruktion, Konzentration und Konsequenz in der Skulptur’, 11.

[17] Gregor H. Lersch, “‘Art from East Germany?’–Die internationale Verflechtung der Kunst in der DDR: Ausstellungen, Rezeption im Ausland, Transfers”, diss. Europa-Universität Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder), 2021, 94, https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-euv/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/906/file/Lersch_Gregor_H.pdf. Translation author’s own.

[18] Lersch, “‘Art from East Germany?’”, 151–52.

[19] See https://www.mz.de/lokal/halle-saale/einheit-der-arbeiterklasse-und-grundung-der-ddr-dieses-wandbild-soll-saniert-werden-1758843.

[20] Lersch, “‘Art from East Germany?’”, 89.

[21] Marcus Andrew Hurttig, ‘The International Aspirations of the Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig with Regard to Its Collection and Exhibition Programme between 1949 and 1989’, in Sithara Weeratunga & Marcus Andrew Hurttig, eds., Re-Connect: Kunst und Kampf im Bruderland – Art and Conflict in Brotherland (Munich: Hirmer, 2023), 37–54, here 39.

[22] ‘Ich war in der DDR nicht politisch tätig, gegen meinen Willen erhielt ich jedoch regelmäßig Propagandaschriften direkt aus Kambodscha, die von der kambodschanischen Botschaft verteilt wurden.’ Excerpt from German officer’s written protocol on granting Ky’s citizenship, found in Annerose Ky’s home.

[23] Interview with Linda and Annerose Ky and the author, 2024.

[24] Schwarz, ‘Konstruktion, Konzentration und Konsequenz in der Skulptur’, 10.

[25] Artist’s statement on Begegnung [encounter], found in Annerose’s home.

[26] Jürgen Otten, ‘Stählern und doch nicht hart’, Berliner Zeitung, 22 November 1995, https://www.berliner-zeitung.de/archiv/skulpturen-des-weltkuenstlers-songhak-ky-aus-kambodscha-im-constanze-pressehaus-staehlern-und-doch-nicht-hart-li.491570.

[27] “Das Wesen der asiatischen Kunst, die in ornamenthaft aufgefaßter Körperlichkeit die Reduktion und Konzentration auf das Wesentliche erreicht, wird aufgebrochen, indem der Künstler ständig von der Symmetrie in die Asymmetrie wechselt, ornamentale und freie Auffassung miteinander in eine Diskussion, einen spielerischen Gegensatz zweier gegeneinander stehender Gestaltungsprinzipien bringt und damit kulturelle Differenzen reflektiert.” Ralf Frank Hartmann, ‘Song Hak Ky – Skulptur im kulturellen Diskurs’, in Song Hak Ky Skultpur (Berlin: Constanze Pressehaus, 1996), 6.

[28] The rise of right-wing extremism and anti-immigrant sentiment in post-unification Germany was particularly evident in violent attacks and riots that explicitly targeted Black and brown migrants, such as those in Hoyerswerda in 1991 and Rostock-Lichtenhagen in 1992.

[29] This text could not have been completed without the help from and access to private archival materials generously provided by Linda Ky and Annerose Ky. I would also like to thank other Cambodian friends of Songhak Ky like Sonny Thet, Vann Tay Bean, Eng Seng Thay, Vannavuth Khieu, researchers like Roger Nelson, Jochen Voit (project ‘Gewalt und Freundschaft: Kambodscha und die DDR im Zeitalter der Ideologie’), Phuong Phan (project ‘Where is my karaoke?’, with me), Doreen Frauendorf, Carmela Kahlow and Katharina Loos (librarian and archive team of Kunsthochschule Burg-Giebichenstein), Moritz Henning (project ‘Contested Modernities: Postcolonial architectural modernism in Southeast Asia’), Rosa Cordillera A. Castillo, Hai Nam Nguyen, and of course the HKW team, in particular: Paz Guevara, Can Sungu, Cosmin Costinaș, Carlos Maria Romero aka Atabey, Sophie Genske, Lama El Khatib, Eunice Fong, and Eric Otieno Sumba, for having helped in my research or supported this collaboration with HKW, directly or indirectly.