Photo: Can Sungu

The first time I came across the Tashkent Festival of African, Asian, and Latin American Cinema was in the text ‘Tashkent '68’ by Rossen Djagalov and Masha Salazkina. It piqued my curiosity and made me want to learn more about the festival and the internationalist film networks it fostered. Gradually, I developed the Destination: Tashkent project at HKW. Over the past two years, I traveled to Tashkent three times for the project. While each journey from Berlin to Tashkent had slight variations in its route, I always had to transit via Istanbul—the city where I was born and raised, which today hosts a significant Uzbek community who come to Turkey for work or studies.

Photo: Can Sungu

Known as Cinema Palace or Panorama during Soviet times, this venue was later renamed Kinochilar uyi (House of Cineastes) in Uzbek, and recently became Milliy kino san’ati saroyi (Palace of National Film Art). Its grand hall, with 1,890 seats, was the main venue of the Tashkent Festival, hosting opening ceremonies and award presentations. Completed in 1964, the building is one of the most striking examples of Soviet modernist architecture, which is widely visible in Tashkent. It also boasted one of the first cinemascope screens in Central Asia, making it a pioneering space for screening films in the widescreen format.

Can Sungu. Photo: Malve Lippmann

My research in Tashkent began at the Cinema Palace, which today comprises several cinema halls, a café, and a museum. The museum’s permanent exhibition features images from the historical Tashkent Festival, Uzbek films, and other exhibits about the country’s film history – all presented from the “official” state perspective.

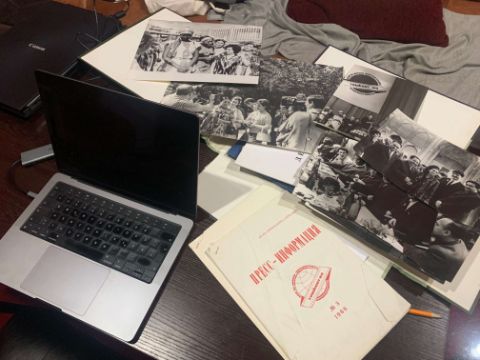

Photo: Can Sungu

The museum in the Cinema Palace allowed me to explore the archive of the Tashkent Film Festival, which includes numerous photos, original documents, and magazines from that era. Thanks to the hospitality of the staff, I had a small yet peaceful space to conduct my research. I was surprised to discover that Soviet press coverage of the festival was not only in Russian but also in Uzbek. Among other items, I found invitations to special festival events, such as ‘Africa Liberation Day’, as well as menus informing festival guests about lunch and dinner options.

Photo: Can Sungu

Uzbek cuisine showcases some of Central Asia's most iconic dishes, like plov, manty, and samsa. In recent years, Uzbek cuisine has gained recognition in Berlin as well. This culinary tradition is shaped not only by the region's unique geography and climate, but also by its history and migration patterns. In Uzbekistan, people often visit restaurants labeled Milliy Taomlar (national dishes). Pictured here is a serving of norin, a dish popular in Tashkent made with thinly sliced dough, horse meat, and onions. It is typically accompanied by a rich broth and, of course, choy (black or green tea).

Photo: Can Sungu

Many food stands can also be found at Chorsu, Tashkent's large bazaar. In a semi-open area, vendors sell Uzbek national dishes and serve them at communal tables behind the stalls. Under the bazaar’s iconic blue-green domes, one can find meticulously organized sections offering dairy products, fresh meat, fruits, vegetables, spices, nuts, and dried fruit. Designed in the late 1980s by architects Vladimir Azimov and Sabir Adylov, these circular halls remain a vital space for Tashkent residents. Nearby, the Kukeldash Madrasa, built in 1570 by Dervish Sultan as a school, stands as a historic landmark. Stairs within the bazaar lead down to the metro, where some of the city's finest mosaics can be found.

Photo: Can Sungu

Tashkent’s metro, opened in 1977, was the first in Central Asia. Each station is dedicated to a specific theme, often tied to its name. The Kosmonavtlar station on the Oʻzbekiston line celebrates space exploration, honoring Soviet cosmonauts Yuri Gagarin and Valentina Tereshkova—the first man and woman in space. It also features depictions of Icarus and Ulugh Beg.

.JPG)

Photo: Willie Schumann

From September 26–29, 2024, the first part of the Destination: Tashkent project took place in cooperation with the Goethe-Institut in Tashkent. The programme focused on the history of the Tashkent Film Festival as well as contemporary film festivals and cultural spaces that have emerged in recent years in Tashkent. The four-day program included screenings, panels, dinners at various venues, and a city tour exploring Tashkent's history and architecture.

Photo: Willie Schumann

The guest of honor at the Destination: Tashkent festival was Ali Khamraev, one of Uzbekistan's most renowned filmmakers, who was actively involved in organizing the historical Tashkent Festival. On the opening night, Samurai Rebellion by Masaki Kobayashi, one of his favorite films from the festival, was screened, followed by a conversation with him. As an eyewitness, he shared insights about the festival and his ambivalent relationship with Soviet authorities, who often censored public screenings of his films.

Photo: Willie Schumann

The film and discourse program in Tashkent was simultaneously translated into Uzbek, Russian, and English. The practice of live translation has a history in Tashkent. At the multilingual Tashkent Festival, translation was a particular challenge as only a few films were subtitled. The organizing team decided to offer live translations into Russian (via loudspeakers) and into English, French, Spanish, and Arabic (via headphones). As historian Elena Razlogova has described, translators at Tashkent reshaped the films, creating a live performance layered over the original soundtracks.

Photo: Can Sungu

As part of the Destination: Tashkent festival, Tashkent-based urban researcher and designer Alexander Fedorov led a city tour that explored the modern history of the city through its architecture. The meeting point was Hotel Uzbekistan, a key site for participants of the historic festival, which hosted numerous international guests. The hotel remains operational today and, apart from some renovations to its façade, is largely unchanged.

Photo: Can Sungu

The MOC Hub, one of the venues for the Destination: Tashkent project, is located in the Жемчуг (pearl) residential complex, completed in 1985 by architect Odetta Aidinova. This sixteen-story residential tower is a unique example of Soviet Brutalism. It features an inner courtyard on every floor, communal spaces, a semi-public garden, and a terrace accessible only to residents. The design draws inspiration from the traditional Uzbek mahalla (neighborhood) and reinterprets this concept vertically.

Photo: Can Sungu

The festival dinner took place in the courtyard of the Жемчуг residential complex, where festival participants and residents enjoyed Uzbek plov. Known as plov outside of Uzbekistan, this rice dish is called osh locally and is often prepared for festive occasions. There are many regional variations of osh, but carrots, beef, and cumin are essential ingredients.

Photo: Willie Schumann

Inspired by the historic Tashkent Festival, the dinner aimed to create a convivial space where participants could meet and exchange ideas. Eyewitnesses recount that the historic Tashkent Festival reached its peak during moments of eating, drinking, and celebration. These moments contributed to the festival's legendary status, particularly because of its renowned hospitality. ‘What happens in Tashkent stays in Tashkent’ almost became the festival’s unofficial motto, offering official delegations a rare opportunity to act without the usual fear of surveillance or espionage so prevalent in Soviet times.

Photo: Willie Schumann

One of the highlights of the Destination: Tashkent festival for me was the screening of Emitai by Ousmane Sembène on the rooftop terrace of the Жемчуг residential complex, organized by the MOC team. The film was introduced by Aboubakar Sanogo and live-translated into Russian and Uzbek. The breathtaking view of the city and hot tea accompanied this open-air screening in this extraordinary location.

Photo: Can Sungu

The archive exhibition at the Ilkhom Theater presented selected photos from the collection of the Uzbek film and photo archive, as well as additional items sourced from private archives and flea markets. Souvenirs such as porcelain plates or tea sets were particularly popular and often featured the Tashkent Festival logo. Guided by Elyor Nemat, the exhibition provided an overview of the festival’s history and showed how specific stagings in the photographs visually conveyed the festival’s ideological character.