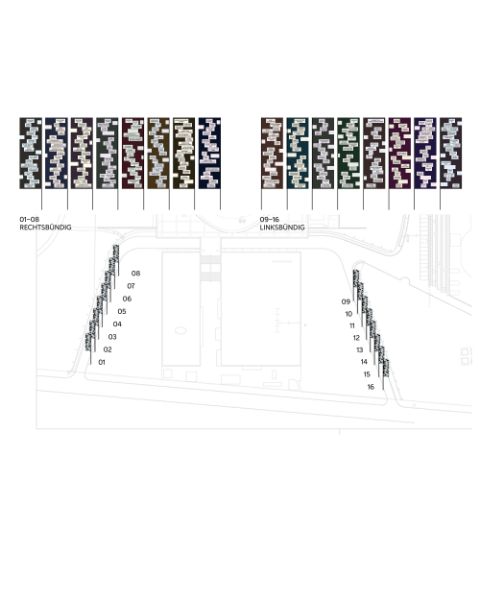

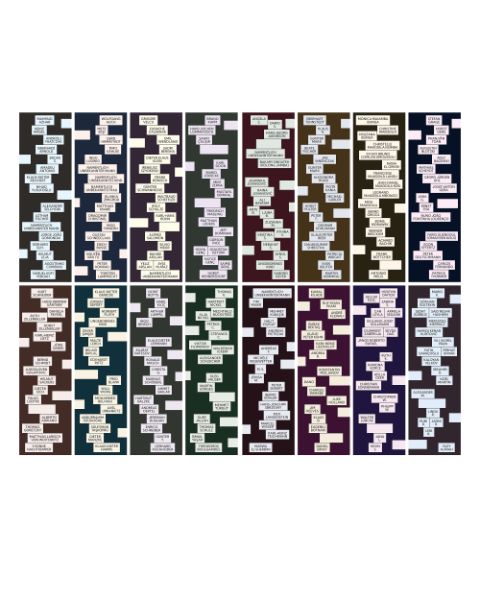

Sixteen flags bearing the names of people known to have lost their lives to right-wing violence. Including those not recognized by the state as victims of right-wing crimes, even though the facts speak for themselves. At the time of the installation, there are 264 names—plus many blank lines, left empty for those whose names we do not know and for those whose deaths we must still fear. The flags stand in a wide semicircle. The wind blows, keeping them in motion. The light makes them visible. Two hundred and sixty-four names.

As I write this, four more names of victims of very probable right-wing violence are added to the list: Kancho and Katya Zhilova and their daughters Galia and Emily, who died in an arson attack in Solingen on 25 March.

Let’s imagine that these flags stake out a space, constituting a parliament where those robbed of their lives would have a voice, where they could speak. Let’s imagine they would claim a space of grievance and complaint (Klage), a space of acknowledgement and a space of making demands. This parliament would be a try-out, the starting point for a space of remembrance that would still need to be established, taking the side of those who have yet to be named as victims. Such a space would be perpetually evolving, never fixed, its bounds remaining open.

Before we can conceive of such a process, we need to know where we stand. Since 1990, at least 264 people have lost their lives to right-wing violence in Germany, and now probably four more. If we go back further, back to the defeat of the Nazi regime, the figure is higher—in excess of 300 murders.

Chronicling neo-Nazi violence and assembling the names of all those who have been murdered raises many questions. Which authority judges who should be recognized as a victim of a right-wing crime? On the basis of which criteria? Official statistics on politically motivated violence only go back to 2001. In addition, the way a crime is classified depends on the officers investigating the case. If they see no political motivation, it will be hard to prove a right-wing motive for the murder at a later date. Police statistics list crimes only as solved or unsolved, and it’s not easy to retrospectively expand or modify the content of case files.

Those affected by right-wing violence are often not listened to, and in many cases they are prejudged. After the racist murder of Halit Yozgat on 6 April 2006 in Kassel, his family joined with friends and family of Enver Şimşek and Mehmet Kubaşık, two others murdered by the same right-wing network, to organize a demonstration. Their banners called for ‘No 10th victim!’ because they, long before the authorities were willing or able to do so, had identified a clear connection between the nine murders committed by the NSU. Most of the 4,000 people who attended the demonstration had experienced racism themselves, reflecting the extent to which the majority within society were either not listening or even actively ignoring this issue.[1]

In addition, antifascist research groups often know more than official investigators and the judiciary. In the case of the right-wing murder of the CDU politician Walter Lübcke, it subsequently emerged that the two culprits had known links with right-wing demonstrations and networks. This knowledge came from citizens’ research groups and not from the authorities.

Drawing up lists and chronicles is a technique that has a special history in Germany. In any case, it is a way of producing inclusion and exclusion along lines determined by specific criteria. It makes sense, then, to go further and to keep asking more questions.

In 2024, twenty-two people were killed by the police. Some of them were mentally ill, some were affected by racism, poverty, or homelessness. What are the criteria for dealing with these deaths? How can police violence be described in anti-discriminatory terms? Can a single act by a person in uniform be considered in isolation, separate from that person’s political views and prejudices?

In 2023, a woman was murdered almost every day in Germany. Which criteria might be applied when deciding whether or not to include the names of these women in a chronicle of right-wing violence? When they are being killed by individuals who often have a misogynistic or fundamentally right-wing worldview?

In the first three months of 2025, 386 people have already died while attempting to cross the Mediterranean as refugees. Do political notions of “Fortress Europe’ go so far that these individuals could be named as victims of structural and deliberately perpetrated right-wing violence? At what point does authoritarian politics count as right-wing violence? What ideas and self-critical knowledge does a society derive from this? In order to classify a murder as right-wing, does there need to be a clear link to the ideologies of National Socialism? Or is an avowal of authoritarian regimes and politics sufficient? Can right-wing chat groups and browser histories, hate-filled songs and memes be used to adequately describe why people have to die?

On 25 March 2024, Kancho and Katya Zhilova and their daughters Galia and Emily were killed in Solingen by an arson attack that left 21 people injured, some of them severely. The culprit was arrested and is currently on trial. Immediately after the attack, citizens’ initiatives called for racism to be considered as a possible motive. Those investigating the case ruled this out, however, until the joint plaintiff Seda Başay-Yıldız called in court for a revaluation of the evidence, including photographs from the culprit’s milieu with pointers to right-wing ideologies and his similarly revealing Google search history, after which a search of the culprit’s hard drives was carried out. This search turned up openly neo-Nazi propaganda. When (in spite of evidence to the contrary) murder investigations don’t take right-wing ideology into consideration, then these killings are not prosecuted as crimes with a right-wing motive, nor are they counted as such. The problem, then, is that the (prior) knowledge of the police, the authorities and the courts concerning racism, anti-Semitism, and right-wing violence is not the same as the knowledge of those affected, of the survivors, and of the initiatives and activists acting in solidarity with them—a knowledge informed by experience. Which is why these groups and individuals present their own lists and chronicles in opposition to the ‘official’ account recognized by the state. Their studies include cases where a right-wing motive is considered to be beyond doubt in spite of the lack of official recognition. They also include cases where a right-wing motive is highly probable. And then there are the unknown victims of right-wing violence and the crimes of which we are as yet unaware.

To remember means to acknowledge

How can the continuities of right-wing violence in post-Nazi Germany be portrayed when until 1990 the victims were not recognized as such by the state? How can the gaps and omissions be discussed and made visible? Who are these people? Who have we forgotten?

Remembrance in solidarity often takes place without the legitimation of institutions and the state, and it always addresses its own modes of representation.

The installation of the flags seeks to set in motion a process that does not simply present a finished place of remembrance, but that publicly asks how such a place should be constituted.

The arduous task of chronicling right-wing terrorist murders and compiling the names of the dead is performed by the bereaved, by journalists and activists, and by initiatives of solidarity.[2] This work has produced books, social media platforms, websites, archives, and works by artists. All of them counter the incomplete official lists of victims recognized as such by the state with their own research and the demand for acknowledgement so that no names are forgotten. In solidarity with the victims, this work on a chronicle of right-wing violence asks questions about the criteria for state recognition, contrasting them with the experience-based knowledge of those affected.

In order to render this complex work visible and transparent, future versions of the place of remembrance will also allow these struggles, demands, and activist research to be addressed by gathering and presenting names and biographies. A key additional objective here is to acknowledge the work done by the bereaved and the initiatives that support them.

To remember means to speak out

For some, it seems like everything that can be said on this topic has already been said. And it’s true that a great deal of material has been presented. But was anyone listening?

If not, what should be added to all the speeches, essays, and studies?[3]

The problem has been highlighted in a variety of ways: those affected have supplied numerous clear, fact-based analyses of the events involved in these murders and terrorist attacks, and of the structural failings of the police, the authorities, and of politicians. They have called for complete clarification and justice, for the victims to be compensated, for the files to be published. In many cases, their experience as direct or indirect victims of right-wing violence also led them to adopt clear positions: they called for fundamental changes in police work and demanded that Nazi networks be exposed, disarmed, and banned. In thirteen parliamentary inquiries at both state and federal level, they gave accounts of their experiences and offered their assistance in addressing the failings of the authorities. And the failings of society in general, where they see an urgent need for improvement in the sense of genuine justice: changes in the law concerning the prosecution of acts of violence against migrants; long-term investments in a range of progressive educational programs to tackle racism and anti-Semitism, rather than increasing police budgets; training schemes for the police to deal with discriminatory and racist tendencies; long-term psychological support for survivors and family members, but also for first responders; financial compensation and support via social services and legal aid.[4]

But was anyone listening?

At the sadly numerous events marking the anniversaries of right-wing murders, they speak as experts, doing the emotional work, taking the trouble and the time to face these terrible events, in front of an audience, again and again, and to share the insights and viewpoints they have gained from these experiences with all of those present.

Has their message gotten through to the relevant authorities?

Knowledge derived from personal experience is of great value when coming to terms with such violence. What needs to happen before this knowledge can be genuinely acknowledged on a structural and political level? Can we hear the difference between symbolic recognition and genuine recognition that also exists in material terms? The difference between today’s awkward handshakes and compensation or changes to the law, as well as structural changes in the police, the judiciary, the authorities, the media, and politics?

What might be said about a city’s official culture of remembrance, for example, after politicians in Hanau told Emiş Gürbüz, who lost her son Sedat Gürbüz in the right-wing terrorist attack, that she should have been thinking about her application for German citizenship when she dared, at the official commemoration event, to state that the police and the city authorities had a share of responsibility for her child’s death?

There have been countless press conferences, films, and theatre plays. People touched by right-wing violence have written books, founded educational initiatives and spaces, they have taken part in panel discussions, been on television, fought for memorials, been named in songs, there are commemorative events, there are even plans for an NSU documentation centre—there is no shortage of opportunities to learn from the survivors, from the bereaved, from those affected. They never stop speaking.

Have these people been heard, in a society where, unlike tons of weapons and ammunition from the stocks of the police and the army, right-wing terror and violence have not yet disappeared? Have they been heard in a country where self-proclaimed neo-Nazis have gun licenses or even work as ‘friendly faces of National Socialism’ in Germany’s parliament, the Bundestag? In a country where hundreds of neo-Nazis enjoy full freedom of movement in spite of warrants having been issued for their arrest? Have these people’s demands been heard?

As long as this doesn’t change, society will not change the conditions under which right-wing terror flourishes.

To remember means to listen

How drastically would investigations into the perpetrators of right-wing violence change, for example, if the authorities took seriously the words of Ibrahim Arslan, a survivor of the arson attack in Mölln?

Arslan has long demanded that those affected by right-wing violence should not be treated as mute extras but as the main witnesses and as experts on the events in question.[5] This concerns not only practices of memory, which should be organized either by those affected or with their direct involvement, but also investigations into the perpetrators of crimes against migrants, which should always take the possibility of a racist motive into consideration.

How often have survivors and victims themselves been blamed by investigators and by the authorities?

As a result of the racist defamation of an entire neighbourhood,[6] with claims of ‘clan-based crime, drug dealing, and underworld connections’, plus a heated media debate focussed on the migrant population of Keupstrasse in Cologne, for seven years (!) the victims of the 2004 nail bombing were suspected of having carried out the attack themselves. Innocent victims were interrogated, suspected, and humiliated by the authorities until, in 2011, what they had long assumed turned out to be the case: right-wing perpetrators were responsible. The culprits had even been identified by one victim at the scene of the crime. But no one had listened.

The NSU murders in Germany and the events surrounding their investigation and prosecution brought many horrifying revelations. With regard to the active silencing of those affected, it shows how a group of perpetrators with anti-Semitic and racist motivations and ideologies were able to pick their victims without being discovered by investigators, thus destabilizing a whole community of migrants and letting them know: you are not safe here. If one considers the silencing of the victims by the authorities, the media, and the public in connection with the anti-Semitic and racist ideology of the murderers, one understands how the investigating authorities—and in particular the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution—became a tool in the hands of these perpetrators.

This insight has generated an irrevocable mistrust towards the institutions of the state, since all of those directly affected and all of those who know that they, too, are potential targets have experienced in twofold fashion how vehemently their participation in this society is being attacked and opposed.

To remember means to change

In spite of this, the struggles by victims, survivors, family members, and initiatives of solidarity have achieved something decisive: they have enabled those no longer able to play an active part, on account of their violent death, to make an impact nonetheless, over a period of decades. Those affected have formed an alliance, they encourage each other, they listen to each other, they acknowledge the pain of each other’s loss, but also each other’s demands for clarification and justice, for societal change. They stand firm against a separation of the fights against anti-Semitism and racism. In this way, they have denied the violent right-wing perpetrators what they wanted—the total disappearance of these human beings. They name their names and tell their stories. In this way, they have, at least in part, thwarted the hate. They have given the dead an ongoing life and a voice. This is a reality.

This reality sparked an important social movement in Germany.

In recent years, many people have been reached by calls for change, by processes of mourning together, by the creation of spaces that centre the viewpoints and voices of the bereaved and of survivors. There have been large and small demonstrations and events attended by a broad cross-section of society. Many political groups have integrated the focus on the viewpoint of victims into their work. The result was an audible echo, and there were moments that resembled societal change, sometimes even transformation. A society of the many and the few who were vehemently and firmly against any illegalization of people, against the politics of isolationism, against degradation and classification by politics, police, authorities, borders, and laws. Sometimes it even felt like these demands were being heard. Sadly, this is not the reality. Especially not for the declassed.

In line with this movement, the place of remembrance with the flags seeks to listen and to understand. How to save what has already been achieved? How to secure what will be important in times to come? There is much to be defended.

The dead can no longer speak, they were stripped of their right to autonomy and free speech. They were robbed of the possibility of doing what they might have wanted to do with their lives. They were deprived of something every human being is entitled to: to make an impact as one sees fit, to speak, to meet other people.

What if they were to come together nonetheless? What if they carried on calling on others to gather?

What if they continued to speak? What would they say about a society that didn’t protect them?

Anyone wishing to hear them, anyone wishing to understand them must listen to the survivors, to the bereaved. What they say, what they call for, how they struggle, how they take care of each other. What they need.

Translated from the German by Nicholas Grindell

[1] Ayşe Güleç, Johanna Schaffer, “Empathie, Ignoranz und migrantisch situiertes Wissen: Gemeinsam an der Auflösung des NSU-Komplexes arbeiten,” in Juliane Karakayali, Çagri Kahveci, Doris Liebscher, Carl Melchers (eds.), Den NSU-Komplex analysieren: Aktuelle Perspektiven aus der Wissenschaft (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2017), 57–80.

[2] See Ali Şirin (ed.), Erinnern heißt Kämpfen. Kein Schlussstrich unter unsere Stimmen (Münster: Unrast Verlag, 2024); Paula Blickle, Frank Jansen, Heike Kleffner, Johannes Radke, Julian Stahnke, Toralf Staud, “Todesopfer rechter Gewalt,” Zeit Online (September 2020), https://www.zeit.de/gesellschaft/zeitgeschehen/2018-09/todesopfer-rechte-gewalt-karte-portraet; Amadeu Antonio Stiftung, “Todesopfer rechter Gewalt,” https://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/todesopfer-rechter-gewalt/; Thomas Billstein, Kein Vergessen. Todesopfer rechter Gewalt in Deutschland nach 1945 (Münster: Unrast Verlag, 2020); Harry Waibel, Rechte Kontinuitäten: Rassismus und Neonazismus in Deutschland seit 1945. Eine Dokumentation (Hamburg: Marta Press, 2022).

[3] See https://19feb-hanau.org/2023/01/25/rassistischer-anschlag-in-hanau-verschlossener-notausgang-ohne-konsequenzen/.

[4] “Hanau – 5 Jahre danach: Opferberatungsstellen ziehen nach dem rassistischen Anschlag von Hanau eine bittere Bilanz und fordern eine langfristige Beratungsstruktur für Anschlagsbetroffene,” https://verband-brg.de/hanau-5-jahre-danach/.

[5] “Opfer und Überlebende sind die Hauptzeugen des Geschehenen, wir sind keine Statisten,” https://www.nsu-watch.info/2016/11/opfer-und-ueberlebende-sind-die-hauptzeugen-des-geschehenen-wir-sind-keine-statisten/.

[6] Dostluk Sineması (ed.), Von Mauerfall bis Nagelbombe (Berlin: Amadeo Antonio Stiftung, 2014).