“Loss gives rise to longing, and in these circumstances, it would not be far-fetched to consider stories as a form of compensation or even as reparations, perhaps the only kind we will ever receive.”

—Saidiya Hartman, ‘Venus in Two Acts’[1]

In the final room of the British Pavilion[2] at the 2024 Venice Biennale, black-and-white archival images appear on six screens: a well-known photograph from the Vietnam War of a woman in distress, trying to get herself and four small children across chest-high waters; a pensive girl holding her chin, looking away from a beat-up boat; American GIs torching an attap house; a close-up of the ace of spades cards that American soldiers infamously put on the bodies of Vietnamese they had killed.[3] In another constellation of colour images that come onto the same screens, an East Asian woman stands in a lake in the British countryside, next to an abandoned boat—not unlike that in the earlier photograph of the Vietnamese boat-person girl—captured from multiple angles. On the middle screen is a toned monochrome photograph of a plane spraying defoliant over tropical vegetation, possibly in Vietnam.

The accompanying wall texts, cast as ‘cantos’, as in songs or poems, frame the work of artist John Akomfrah on view as prompted by his ‘long-standing motivations in addressing landmark moments in British history with a rigorous critical lens’. It ‘captures pivotal moments in the history of colonized countries… across Africa and Asia’, as well as glimpses as to how the world’s current ecological crisis has its roots in colonial wars, like the American use of pesticides such as Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) in the Korean War and chemical weapons in Vietnam. The text notes how Akomfrah ‘repositions narratives’ and ‘approaches these narratives through the lens of the diasporic community in Britain, intertwining personal memories with the collective consciousness of those displaced by political crisis, in order to highlight the interconnectedness of enduring legacies of colonialism’. To have a figure like Akomfrah, a pioneering artist of colour who is critical of Britain’s treatment of colonies and diaspora, show in the British Pavilion, and to hear—in person—dignitaries at the pavilion’s opening ceremony give fist-punching speeches about representing black and brown bodies felt like a milestone moment.

But Malaya is missing.

Even in this encyclopaedic interrogation of colonial histories—Britain’s and that of other imperial powers like Belgium and the United States—Malaya remains occluded. In a presentation that cites, in imagery and text, British brutalities in the Mau Mau uprisings in Kenya, the Indian Partition, and Nigeria’s independence movement,[4] refracting them through the faces and bodies of present-day diaspora in the UK, it seems strange, and perhaps unconscionable, to leave Malaya out.

After all, Malaya was the longest war Britain fought overseas after World War II. The twelve-year war (1948–1960) in which the British quashed a Communist-led insurgency in its colony of Malaya—present-day Malaysia and Singapore—has had an outsized importance in the history of warfare, its influences reverberating till today. Britain’s counter-insurgency strategies in Malaya, including defoliant use, forced relocation of rural populations, mass arrests and deportation, and the zoning of ‘Black’ and ‘White’ areas, have been written into western military manuals and gone on to influence campaigns in Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan and even Gaza, scholars note.[5] If nothing else, Malaya’s occlusion from Akomfrah’s iconic installation shows how that war is entirely missing from Britain’s public memory[6] and the global discourse around decolonization wars. In the former colonies of Malaysia and Singapore, the memory of the Malayan war is cast, as seen in two state-built monuments,[7] as a singularly successful smashing of a Communist insurgency, but little-discussed otherwise.[8]

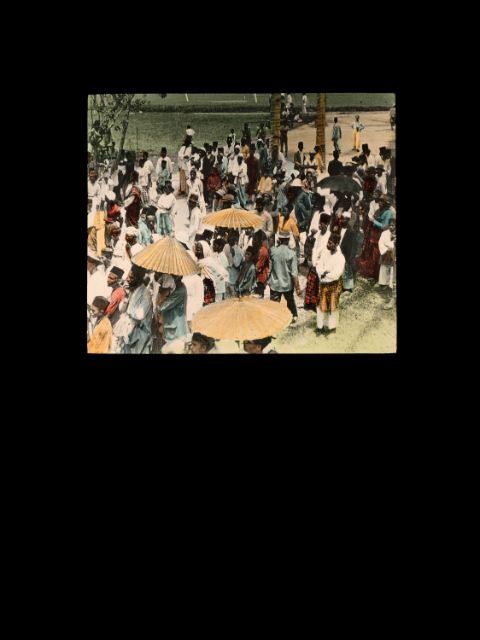

Over the past decade, this forgotten war in Malaya has been the centre of my research and art-making, resulting in multiple works, the latest of which was installed in the HKW’s Forgive Us Our Trespasses exhibition (14 September–8 Dec 2024).[image 1] My project, ‘One Day We’ll Understand’,[9] which also resulted in an art practice-based PhD, uses artistic research and art-making as methods to re-remember and memorialize the Malayan war.[10] I seek to make visible and unmute characters and narratives hidden and silenced in the official archive, to intervene with official historiography and what public memory there is of this war, but also to contribute a different, more liminal, sort of knowledge to historical study. The artistic work, which spans photographic and filmic installation, book-making,[11] and performance, can be thought of as multiple modes of archiving and counter-archiving the Malayan war. Then, using methods more speculative and akin to ‘critical fabulation,’[12] I seek to transcend the archive and conjure memory in a space of imagination and futurity. Reading the colonial archive along and against its grain, I delve between and beyond it.

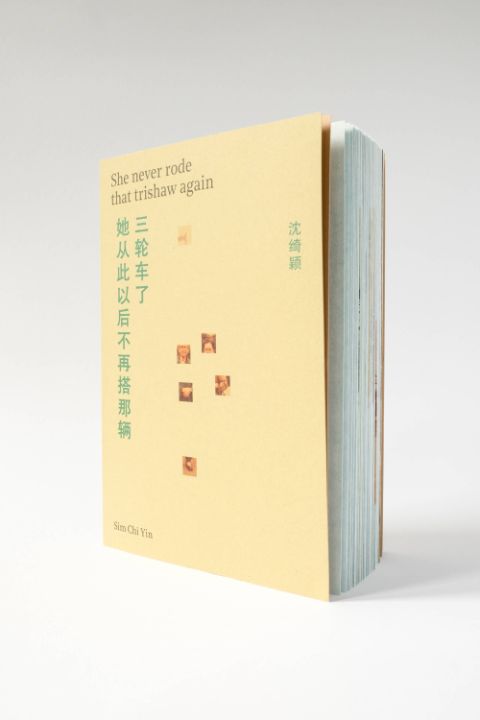

In working through my family history to get to larger questions of memory and historiography, I map the personal onto the geopolitical. During the ‘emergency’, my paternal grandfather Shen Huansheng, an educator and newspaper editor active in the anti-colonial movement, was deported to China by the British alongside 30,000 to 40,000 other leftist Malayans. This mass deportation—still little researched, even by academics—led to varying fates for its subjects/victims.[13] In the case of my grandfather, who was among the first batches of deportees, being shipped to China in mid-1949 as that country was in the final months of its civil war, meant almost certain death. He was executed by Nationalist Kuomintang soldiers in July 1949—as local archives documented—just weeks shy of the Communist victory in China. Granddad, who went on to be memorialized as a Chinese Communist martyr with his own three-metre-high obelisk in our ancestral village in Guangdong, southern China, was never spoken about again by his wife, mother, and the five children left behind in Malaya. Their silence—with its implicit trauma—sat for six decades within our family, as in so many others who experienced death or disappearance during the Cold War.[image 2]

Granddad floats, apparition-like, into an archive I’ve re-imagined, in The Suitcase Is A Little Bit Rotten (2023),[14] a series of glass plates installed in a constellation of ten works on an oval-shaped plinth in the HKW exhibition.[image 3] He appears, hands on hip, camera slung around his neck, as if an observer in the back of a crowd of Malays; he sits on a log watching elephants at work in a timber yard; he stands on the deck of a ship overlooking the Hong Kong harbour. After a decade of working with imagery from the colonial archive, I wanted to re-imagine through and out of its gaps and trauma. I attempt to cast a ‘disobedient gaze’[15] on the colonial archive, to interrupt its transmission of history—engaging with imagination and its emancipatory potential as a way out of the entrapment of the past. In this series, I reappropriate nineteenth- and twentieth-century Magic Lantern slides–once used for scientific, colonial, or Christian missionary lectures and projections—to conjure an imaginary landscape melding the cosmos and historical Southeast Asia. I remake them as glass plates[16] in which time and space are suspended as I teleport Granddad into the same realm as my toddler son, who inherited his name. In a sort of time travel in the archives, these two characters inhabit a re-imagined Southeast Asia.[17] What, beyond a name, could a child inherit from our pasts? Can we remake the violence and trauma-filled colonial archive before passing it on to the next generation? Do history and time travel in circles?[18]

Like a wormhole, a colonial-era train tunnel appears in the film The Mountain That Hid, inviting us on a journey through multiple registers of time. One screen plays a serendipitous encounter I filmed at that tunnel with a group of selfie-snapping mainland Chinese women hikers, whose comments and conversation hit uncanny notes at the heart of my practice. In parallel, atmospheric scenes unfold of the interior of my ancestral house in the mountains of Guangdong, southern China, where Granddad was returned to in 1949 and where he was executed nearby shortly after. There are also the lung-like fibres of an expansive spider’s web undulating in the breeze and a pig hyperventilating in its pen. Bookends of an unfinished history. Does time unfold in a line or does it loop?

The speculative register and the sense that history is unresolved (unresolvable?) binds these two works and makes me think about, and choose to exhibit, them together.[19] Together, they embody my search for a way to translate or transform these difficult, contested histories before passing them on. The two works traverse generations of transnational histories, forming a chronotope of space-time, and opening a portal into questions of memory and time, death and birth, fate and choice, deja vu and kismet.

They build on the earlier chapters of the project, which leaned more on the evidential, the documentary. In Remnants and Requiem [images 4 & 5], I investigated the traces of the Malayan war in the land, objects, and bodies that remained—or went into exile—through making evocative landscape photographs, and a counter-archive comprising still life pictures of left-behind artefacts as well as revolutionary songs the leftist veterans still remember or have forgotten.[image 6] In the work which followed, Interventions, I looked at the entire collection of photographs on the Malayan war in the British Imperial War Museum. I then created a new work reinterpreting them, asking questions of what makes an archive, who is foregrounded or left out, and how all that governs the public memory of a war. Making in-camera collages merging verso and recto of the archival prints, I revealed the indexing within the colonial archive and made new compositions suggesting different, perhaps resistant, readings.[20][image 7]

All these threads, documentary and speculative, culminated in a theatre performance [image 8] I have since developed from the project. Over the course of an hour-long monologue, in which I perform as myself, the narrative shifts modes of my persona: as an artist, a researcher, a granddaughter/daughter/niece, and a mother. It brings to the stage my contemplations around the imprints of time and history, and the workings of trans-generational memory and inheritance. The multimedia performance, developed from an earlier lecture performance,[21] is anchored by projections of my visual work—there are multiple screens on pulleys and the whole floor is a projection surface, too—as well as a soundscape created by percussionist Cheryl Ong.[22] In a sort of duet, the story unfolds and remains unresolved. The frame of a lightbox is a motif through the piece, as are large sheets of paper, which become projection surfaces, alluding to my work in the archives and my unending search. In the closing scene, I am amid a sea of pieces of white paper laid across the stage. They are at first a projection surface where fragments of all the archives I have looked at as well as created flash across in rapid succession in an almost-algorithmic sequence. Then they go blank and become a pristine, bright canvas, a blank slate. With a marker in hand, I crawl all over the floor and write a seemingly-infinite series of clauses that could follow ‘one day we’ll understand…’:

‘that traces remain in land and bodies

the harms of off-shoring unwanted peoples

that colonial practices continue

that some crimes will never be brought to justice

that memory is slippery and histories are governed

that our past shapes us in ways we acknowledge and not

that heartbreak mingled with anger and fear for the rest of her life

the personal costs of war

that some choose to remain silent

that there are pieces of the past we will never know

that things are not black or white

that there are presences we cannot see or speak about

that choices come with consequences

that things come around…’[23]

The lights go out.

In a decade of working on the memory of the Malayan war, I’ve come to see that it, like many other conflicts from the Cold War or earlier, is now beyond juridical and political accounting.[24] In such cases, art might be a key—if the only possible—path now for some sort of restitution or repair.[25] And as Hartman suggests, when the loss is too great and the archival gaps too grave, stories might be a form of reparations.[26] Even as some of us[27] work to thicken the historical record, to counter archive, and complicate the official historiography around the Malayan war and that of others, we can only strive for an assemblage of fragments that remain or conjure into the gaps in the archive.[28] With time, I’m less interested in being mired in the colonial representations and trying to resignify them. Using the ‘master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house’[29] remains a noble task but is perhaps ultimately futile. As an artist and a mother, what preoccupies me now are questions of futurity and inheritance, which require other forms of transposition and transformation, as pathways out of the past—and perhaps the present.[image 9]

[1] Saidiya Hartman, ‘Venus In Two Acts’, Small Axe, Number 26 (vol. 12, no. 2), June 2008, 4.

[2] Listening All Night To The Rain was on view at the British Pavilion as part of the 60th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia, Venice (20 April–24 November 2024), https://venicebiennale.britishcouncil.org/listening-all-night.

[3] For more on this practice, see Charles Brown, ‘Ace of Spades in Vietnam psychological warfare’, History.net, originally published in the October 2007 issue of Vietnam Magazine, https://www.historynet.com/ace-spades-vietnam-psychological-warfare/.

[4] Each of these places and histories were listed in the text accompanying the Akomfrah installation.

[5] See, for example, Laleh Khalili, Time In The Shadows: Confinement in Counter-insurgencies (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013). Also Caroline Elkins, Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022), especially 24–30, in which she charts how the ‘logics of violence’, ‘legal codes’, and ‘time-honed [intelligence] techniques’ circulated across different parts of the empire through the movement of people, top colonial administrators as well as low-level police officers, from ‘South Africa to India, Palestine to Bengal, Ireland to Cyprus and so forth’. She writes: ‘…the movement of people, ideas, practices, and legal systems around Britain’s empire conjures the silks of a spider’s web whose final massive form can be discerned only by stepping back to take in its entirety’. Henry Gurney, high commissioner in Malaya from October 1948 to October 1951, had an instrumental role in Palestine before serving in Malaya where he was assassinated by Communist insurgents. Gerald Templer, who followed him in the role of British High Commissioner in Malaya in January 1952, had also served in Palestine as well as the two World Wars. David A. Charters also writes of how counter-insurgency intelligence practices were passed on from one colonial war to the next by British officers, with lessons learnt from the campaign in Palestine shaping the ‘Malaya model’, which in turn garnered ‘articles of faith in army counter-insurgency doctrine’ that informed the repression of the Mau Mau in Kenya and beyond. See Charters’s, ‘The Development of British Counter-Insurgency Intelligence’, Journal of Conflict Studies, vol. 29 (Spring 2009): 60, 61.

[6] Even as the British (in)famously trying to build a Holocaust Memorial near Big Ben, they have precious few memorials dealing with the memory of their own atrocities in their colonies. See for example Sam Knight, ‘Why Is It So Hard To Build A Holocaust Memorial In London?’, The New Yorker, 2 Jan 2025, https://www.newyorker.com/news/letter-from-the-uk/why-is-it-so-hard-to-build-a-holocaust-memorial-in-london.

[7] The Tugu Negara or National Monument, in the heart of Kuala Lumpur is ‘Dedicated To Malayan Security Forces Members Killed During Emergency’ and was unveiled by the Malaysian king on 8 February 1966. It features four chisel-faced soldiers depicted holding a Malaysian flag, atop other fighters with rounder features and wearing red star berets. In Singapore, in a park a stone’s throw from the neo-classical facade of the Victoria Concert Hall, is a metal slab with the inscription ‘Forging a Nation’, detailing ‘Singaporeans’ struggles against the violence and subversion of the Communist Party of Malaya 1948–1989’ and is ‘dedicated to all those who braved violence and intimidation to fight for a democratic, non-Communist Singapore.’

[8] I discuss Singapore’s and Malaysia’s official memorialization of this war further in a book chapter: Sim Chi Yin, ‘To Singapore and Malaysia With Love: Artistic Legacies of the Malayan Emergency’, in Andrew Ng, Jonathan Driskell, Marek W. Rutkowski (eds.), The Malayan Emergency in Film, Literature and Art: Cultural Memory as Historical Other (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2025).

[9] The line comes from the epitaph on the gravestone of a Scottish plantation owner in Perak, northern Malaya, killed by the Communists in December 1950. It lies in a graveyard known as ‘God’s Little Acre’, in Batu Gajah, Perak. I use it as the title of my project for the multiple meanings it encompasses. Is it an affirmative statement? A tentative proposition? A probing question? Or an expectant aspiration or a wistful hope?

[10] Sim Chi Yin, Traces, spectres and speculation: Art and conjuring post-colonial memory, the “Malayan Emergency” (1948–1960) as case study, PhD thesis, War Studies, King’s College London, 1 Jan 2025, https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/studentTheses/traces-spectres-and-speculation-art-and-conjuring-post-colonial-m.

[11] I am making four books from this project, the first of which was published in 2021. She Never Rode That Trishaw Again, focuses on the life of my grandmother after Granddad was deported and executed for his politics. The book uses her vacation snapshots and postcards to narrate through the life-long trauma she lived with, from his death and the silence she had to observe and impose around him hence. For more, see https://www.printedmatter.org/catalog/62922. The book was also the subject of an installation at Zilberman Gallery Berlin, Swaying The Current, https://www.zilbermangallery.com/swaying-the-current-en-e385.html.

[12] Coined by literary scholar Saidiya Hartman, this method is a critical and empathetic reading of the archive ‘against the grain’ that amounts to what she describes as ‘a combination of foraging and disfiguration’, as ‘troubling the line between history and imagination’. Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2017, W. W. Norton and Company, 2022). See also Hartman, ‘Venus In Two Acts’. The concept is not uncontroversial, particularly among historians—Nell Painter, eminent US historian who also practices as an artist has voiced questions about the method alongside what Black feminist scholar Christina Sharpe has termed ‘wake work’, as a ‘resurrection’ of neglected histories. I have considered these and in my art-making thus far engage with speculative, fabulist methods only in relation to my own family history as well as towards the future, and not the past or with other people’s oral histories and historical material.

[13] Some went on to be persecuted during the Cultural Revolution in 1960s China; others led comfortable lives in the China and Hong Kong working in local government; and yet others suffered as labourers in ‘overseas Chinese villages’ (华侨农场) in southern China. As part of my research, between 2015 and 2019, I did oral history interviews with 40 former Malayan anti-colonial fighters and activists who were deported or exiled, now spread out over Guangdong and Fujian provinces in southern China, Hong Kong, southern Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore.

[14] The title came from a line that my toddler son uttered at age two-and-a-half, conflating some ideas, but delivering a strangely poetic line which suggests the idea of travel but also hints that something is off about the journey.

[15] This is a term coined by art historian Gabrielle Moser, who describes it as a ‘resistant method of historiography’, ‘a mode of looking that refuses the readings imposed on photographs by the colonial state’. Gabrielle Moser, Projecting Citizenship: Photography and Belonging in the British Empire (Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 2019), 2.

[16] These are displayed on replicas of vintage glass negative retouching stands, which date also to the earlier 1900s. In using these and Magic Lantern slides, I perform a sort of double re-appropriation of colonial photographic apparatus to re-narrate the anti-colonial war.

[17] I discussed the idea of time traveling in the archives in the panel ‘Time Travelers: When Artists Remix the Past to Reframe the Present’, artists (from left) Mónica de Miranda, Sim Chi Yin, artist-moderator Ho Tzu Nyen, and artist Kenneth Tam, Art Basel Hong Kong, 23 March 2023, https://www.artbasel.com/stories/time-travelers-when-artists-remix-the-past-to-reframe-the-present.

[18] The writer Ocean Vuong has reflected: ‘Some people say history moves in a spiral, not the line we have come to expect. We travel through time in a circular trajectory, our distance increasing from an epicentre only to return again, one circle removed’. Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (New York: Penguin Press, 2019), 27.

[19] Art historian Gabrielle Moser has written about these two works together, in ‘Mis-Registrations: Sim Chi Yin’s Photographic Transpositions’, Camera Austria International, no. 165 (2024).

[20] For more on these earlier chapters of the work, see the catalogue by Lotte Laub, et al, Sim Chi Yin, One Day We’ll Understand (Berlin: Zilberman Gallery, 2021), https://www.zilbermangallery.com/images/publications/2046550472808769422.pdf.

[21] Methods of Memory: Time Travels in the Archives, at Asia Art Archive in America, New York, 2 December 2022, https://www.aaa-a.org/programs/sim-chi-yin-methods-of-memory-time-travels-in-the-archives.

[22] Shawn Hoo, ‘Theatre review: Artist Sim Chi Yin’s miraculous counter-archive is brought to life’, The Straits Times, 1 Sept 2024, https://www.straitstimes.com/life/arts/theatre-review-artist-sim-chi-yin-s-miraculous-counter-archive-is-brought-to-life.

[23] Sim Chi Yin, One Day We’ll Understand, script for theatre performance, 2024. The theatre performance, which premiered in Singapore in August 2024 and then had its international premiere in Melbourne in February 2025, is a collaborative work with director Tamara Saulwick, dramaturg Kok Heng Leun, musician Cheryl Ong, video artist and sound engineer Nick Roux, lighting designer Andy Lim, technical manager Yap Seok Hui, and executive producer Goh Ching Lee.

[24] Lawyers in Malaysia and the UK have pursued a legal case against the British government over the December 1948 killings at Batang Kali in Malaya for instance, but that has been thrown out of both the British and European Union courts in 2012 and 2018 respectively. Quek Ngee Meng, the Malaysian lawyer leading the Batang Kali case, and the descendants of the 24 civilians killed in 1948, handed a memorandum addressed to then-UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak demanding an official apology from the British government to Britain’s deputy high commissioner to Malaysia David Wallace as recently as December 2023. But it does seem the case has run out of legal road. See for instance ‘Case concerning 1948 Batang Kali killings by British soldiers’, 4 October 2018, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/app/conversion/pdf/?library=ECHR&id=003-6209659-8063572&filename=Decision%20Chong%20and%20Others%20v.%20the%20UK%20-%201948%20Batang%20Kali%20killings%20by%20British%20soldiers.pdf.

[25] I see myself as working towards what Hartman has called ‘an ethical theory of history’ and what Viet Thanh Nguyen has similarly termed a ‘just memory’, one that incorporates ‘an ethics of remembering one’s own’ as well as ‘an ethics of remembering others’. He argues: “This ethics of remembering others transforms the more conventional ethics of remembering one’s own… It expands the definition of who is on one’s own side to include ever more others, thereby erasing the distinction between the near and the dear and the far and the feared… Men and women, young and old, soldiers and civilians, majorities and minorities, and winners and losers, as well as many of those who would fall in between the binaries, the oppositions, the categories.” Viet Thanh Nguyen, Nothing Ever Dies (Cambridge, Mass. & London: Harvard University Press), 9, 12. See also Hartman, Scenes of Subjection, 374 and 127, where ‘an ethical theory of history’ is referred to as a history that takes in the non-history, subterranean history and counter memory.

[26] Scholars Adrienne Huard and Gabrielle Moser offer a useful definition of ‘reparation in its multiple registers—as an act of repair, as the part that has been repaired, as a process of healing an injury, and as an act of justice’. Adrienne Huard and Gabrielle Moser, ‘Reparation and Visual Culture’, Journal of Visual Culture, vol. 21, no 1 (April 2022): 3–16.

[27] I am among a small tide of artists, scholars, and writers from Malaysia and Singapore working to find new ways to retell histories around the ‘Malayan Emergency’. The September 2023 issue of the journal The Margins gathered some of such individuals working specifically on the memory of Malaya; my photographs illustrate the issue. The Margins, ‘The Rainforest Speaks’, Asian American Writers’ Workshop, https://aaww.org/rainforest-speaks/.

[28] Historian Mark Philip Bradley, currently editor of the American Historical Review, a storied journal in the field of academic history, started a new ‘lab’ section in the publication, titled ‘Art as Historical Method’. The section explores the work of artists working on historical subject matter and looks at how artistic methods produce a different sort of knowledge to what historians might. Mark Philip Bradley, ‘Inside the History Lab’, The American Historical Review, vol. 127, no. 3 (September 2022): 1290–1293, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/rhac341.

[29] Audre Lorde, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle The Master’s House (London: Penguin Random House, 2017), 19.